When you think of 1990s hip-hop, images of booming basslines, gritty street narratives, and male MCs dominating the mic might come to mind. But behind those beats and bars, a quiet revolution was happening. Women weren’t just showing up-they were reshaping the sound, the style, and the power structure of hip-hop. This wasn’t a side note. It was the foundation of everything that came after.

The Rise of the Female MC

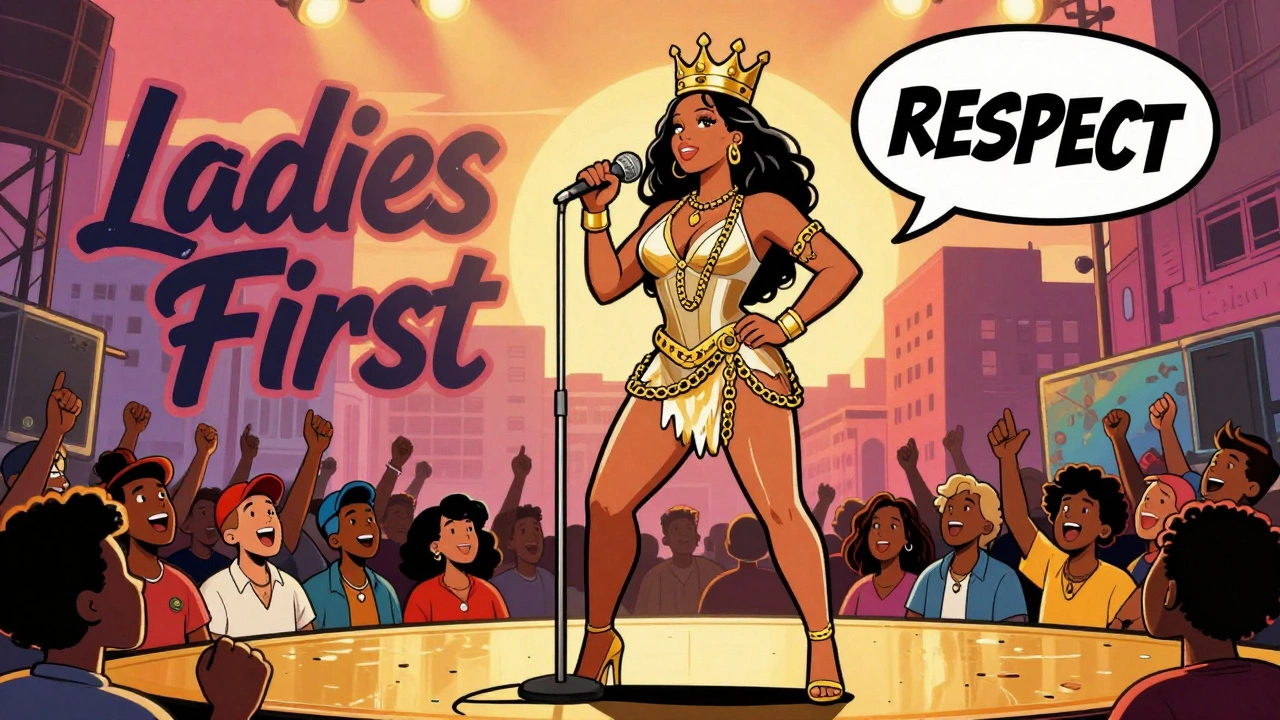

Before the 1990s, female rappers were often treated as exceptions, gimmicks, or guest features. But by 1990, that changed. Queen Latifah had already broken ground in 1989 with her album Let Your Backbone Slide and the anthem "Ladies First." She didn’t just rap-she demanded respect. Her lyrics weren’t about being the "girl in the group"; they were about sovereignty. She proved that a woman could carry an entire album, headline tours, and speak truth without apology. Then came Salt-N-Pepa. Cheryl James, Sandra Denton, and DJ Spinderella didn’t just rap-they turned their bodies into statements. Short shorts, crop tops, bold makeup. They owned their sexuality on their terms. "Let’s Talk About Sex" wasn’t just a hit-it was a conversation starter. They didn’t ask for permission to be loud, sexy, or confident. They just were. And millions followed. Lil’ Kim exploded onto the scene in 1996 with Hard Core. At 15, Foxy Brown had already rapped on LL Cool J’s "I Shot Ya" remix. By the time both dropped their debut albums, they weren’t just competing with men-they were outshining them. Their lyrics were raw, unfiltered, and unapologetically sexual. But they weren’t performing for men. They were speaking to women who’d been told to stay quiet. And then there was Da Brat. The first female solo rapper to go platinum with Funkdafied in 1994. She didn’t need a male feature to sell records. She had the flow, the attitude, and the street credibility. Her presence in the Midwest and South proved that female rappers weren’t just an East Coast thing.Behind the Boards: The Producers Who Shaped the Sound

Most people don’t realize that Missy Elliott was producing hits before she ever dropped her own album. In the early 1990s, she and Timbaland were writing and producing for SWV, 702, Total, and Destiny’s Child. She didn’t just rap-she built the sonic landscapes other artists rapped over. Her production on "Get Ur Freak On" in 2001 was groundbreaking, but it was built on years of unseen work in the studio. She wasn’t alone. Bahamadia, from Philadelphia, started as a producer before becoming one of the first female MCs in the underground scene. She didn’t wait for a label to call. She made beats, wrote hooks, and recorded her own tracks. Her 1996 album Kollage was a masterclass in lyrical precision and production innovation. And then there was Gangsta Boo. As the first woman to officially join Three 6 Mafia, she wasn’t just a featured artist-she was part of the creative core. Her voice on tracks like "Sippin’ on Some Syrup" helped define Memphis horrorcore. She didn’t just rap over beats-she helped craft them. These women weren’t just performers. They were architects. They wrote the melodies, shaped the rhythms, and controlled the direction of songs that became radio staples. But their names rarely appeared in the liner notes as producers. That silence wasn’t accidental-it was systemic.

Regional Power: From Memphis to Brooklyn

Hip-hop in the 1990s wasn’t just New York and LA. It was everywhere. And women were leading the charge in places no one expected. Mia X, signed to Master P’s No Limit Records, became known as the "Mother of Southern Gangsta Rap." She didn’t just appear on albums-she was a cornerstone of No Limit’s rise. Her voice on "Ice Cream Man" and "Ghetto D" gave Southern rap its first major female anchor. She proved that a woman from Louisiana could hold her own against the toughest male rappers in the game. Yo-Yo, mentored by Ice Cube, brought West Coast grit to the scene. While East Coast rappers were battling with words, Yo-Yo was battling with attitude. Her 1991 album Yo-Yo was raw, real, and unmistakably Californian. She didn’t mimic New York. She carved out her own space. Jean Grae, from Brooklyn, never needed a major label. She built a cult following through underground cassettes, mixtapes, and live shows. Her lyrics were sharp, witty, and layered. She didn’t chase chart numbers-she chased credibility. By the time she dropped Attack of the Attacking Things in 2002, she’d already influenced a generation of underground MCs. Each region had its own voice. And each of these women brought something different-not just in style, but in perspective. They weren’t trying to sound like men. They were building something new.Fashion, Identity, and Defying Norms

What you wore in 1990s hip-hop wasn’t just fashion-it was politics. Salt-N-Pepa’s midriff-baring outfits challenged the idea that women had to be modest to be respected. Da Brat’s baggy jeans and baseball caps flipped the script on femininity. Queen Latifah wore crowns, gold chains, and regal robes-turning herself into a queen, not a sidekick. The Lady of Rage wore her natural hair in two afro puffs, a bold rejection of Eurocentric beauty standards. These weren’t random choices. They were declarations. A woman could be sexy and strong. She could be tough and stylish. She could be loud and still be taken seriously. And it worked. Teenagers across the country copied their looks. Fashion magazines ran features on "hip-hop style." Even mainstream brands started borrowing from their aesthetics. The women of 1990s hip-hop didn’t just influence music-they shaped how an entire generation saw themselves.