By the mid-1970s, Nashville wasn’t just a place where country music was recorded-it was where songs were born, sold, and traded like commodities. The city’s songwriting engine ran on a quiet but powerful system: publishing houses. These weren’t flashy record labels or glittering studios. They were modest offices on Music Row, often with just three or four people, managing catalogs of thousands of songs. And behind every hit you heard on the radio was a contract, a royalty split, and a songwriter who showed up every day with a guitar and a demo tape.

The Anatomy of a Nashville Publishing House

In the 1970s, a typical Nashville publishing company looked nothing like a corporate music label. You wouldn’t find a fancy receptionist or a marketing team. Instead, you’d walk into a small office with filing cabinets full of handwritten lyrics, reel-to-reel tapes stacked on shelves, and a desk where a publisher sat, listening to demo after demo. The big names-Acuff-Rose, Tree International, Combine Music-weren’t just companies. They were gatekeepers.Writers signed contracts that gave the publisher 50% ownership of the copyright. In return, the publisher handled everything: submitting songs to artists, collecting mechanical royalties, tracking performances, and paying out shares. The publisher kept 100% of mechanical royalties-the 8 cents per record sold in 1978-then split the rest of the performance royalties equally with the writer. For most songwriters, that meant waiting months, sometimes years, to see a dime.

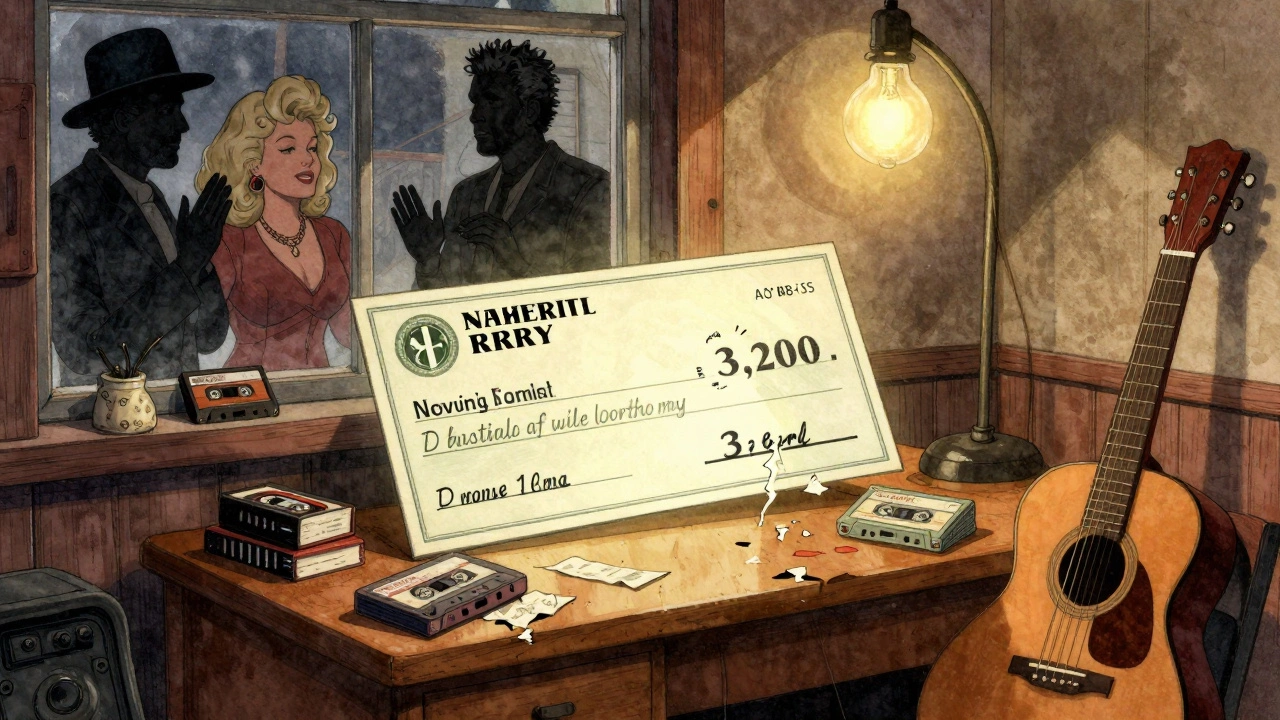

Acuff-Rose, founded in 1942 by Roy Acuff and Fred Rose, was the granddaddy of them all. By 1975, it controlled over 8,000 songs. Tree International, started in 1960, became known for spotting raw talent and pushing songs to stars like Conway Twitty and Loretta Lynn. Combine Music, where one songwriter recalled getting $50 a week in 1974, owned 100% of his copyrights. He didn’t see a royalty check until 1977-when it finally arrived, it was $3,200. That was life-changing money in rural Tennessee.

How the System Worked

The backbone of Nashville’s publishing world was BMI. Broadcast Music, Inc., wasn’t just a royalty collector-it was the invisible hand that kept the whole machine running. Every time a song was played on the radio, in a bar, or on a TV show, BMI tracked it and paid out. But tracking wasn’t perfect. As catalogs ballooned to 5,000-10,000 songs per publisher, errors piled up. By 1979, complaints about missing payments had jumped 37% from 1973.Writers had to prove their songs were worth something. That meant showing up daily at Music Row. No email. No online submission. You brought a handwritten lyric sheet and a tape recorded on a portable reel-to-reel. You waited in line. You listened to rejection after rejection. Billboard’s 1975 survey found only 12% of unsolicited demos got any reply. If you had a connection-someone who knew the publisher, or had played on a session-you might get a deal in 30 days. If you didn’t? It could take 18 months.

The Nashville Songwriters Association International (NSAI), founded in 1967, became the lifeline for newcomers. By 1979, it had grown from 150 members to 1,200. Its workshops taught writers how to structure a chorus, how to pitch a song, how to read a publishing contract. One internal survey found NSAI cut the learning curve by 40%. For many, it was the difference between giving up and getting heard.

Why Nashville Was Different

New York had the Brill Building-tight, factory-style songwriting teams cranking out pop tunes in cubicles. Los Angeles was all about TV and film cues, chasing sync licenses. But Nashville? It was personal. Publishers didn’t just buy songs-they built relationships. They knew which writer had a knack for heartbreak ballads. Which one could write a honky-tonk anthem in an hour. Which one’s lyrics would make Loretta Lynn cry.That intimacy came with a cost. Publishers operated with lean staffs. Dr. Diane Pecknold’s research found many firms had just 3-5 people managing over 2,000 songs. That meant mistakes happened. Royalty statements got lost. Checks got delayed-sometimes 18 to 24 months. As songwriter Mary Ann Kennedy wrote in her memoir, publishers counted on the fact that most writers couldn’t afford lawyers to fight them.

And unlike New York or LA, Nashville didn’t have a Sunday newspaper edition to drive ad revenue. The joint operating agreement between the Nashville Banner and Tennessean kept costs low, but it also meant fewer resources for the music scene. Still, the music kept coming. Country music publishing dominated 68% of the market. Gospel took 15%. Pop and rock split the rest.

The Rise of Independent Publishers

The real shift in the 1970s came when major labels started selling their studios. RCA and Decca had once controlled everything-recording, publishing, distribution. But as artists demanded more control, they began recording in smaller studios, sometimes even in their own homes. That freed up publishing from the record label’s grip.Independent publishers stepped in. Harold Shedd, a producer and label executive, said it best: “The real power in Nashville wasn’t in the big companies but in the independent operators who knew exactly which songs would work for which artists.” These were the guys who had been in the business since the 1950s. They knew the voice of George Jones. The phrasing of Willie Nelson. The emotional rhythm of a Dolly Parton ballad.

One such publisher, Aurora Publishers, didn’t just do music. In 1970, they released Nashville, Sights and Sounds-a book with 40 pages of photos and text, bundled with a vinyl LP narrated by Chet Atkins. It wasn’t just a music book. It was a cultural artifact. That kind of cross-pollination was unique to Nashville. Even Thomas Nelson, the religious publisher, built a new distribution center in the city in 1978, recognizing its growing role as a publishing hub.

The Legacy of the 1970s Catalogs

Today, those old catalogs are worth millions. Sony Music Publishing paid $125 million in 2021 for the Hickory Records catalog-mostly songs written and recorded in Nashville between 1970 and 1979. Analysts estimate these catalogs now generate $85 million a year in global royalties.Streaming services are making it easier to track usage. Gone are the days of manual logging and handwritten ledgers. Now, every spin, every download, every playlist inclusion gets recorded. Goldman Sachs predicts legacy Nashville catalogs will rise 22% in value between 2023 and 2028.

But behind every dollar earned today is a story from 50 years ago. A songwriter in a basement, recording a song on a $20 tape deck. A publisher in a cramped office, listening for the next hit. A royalty check that finally arrived after three years of silence.

Nashville didn’t become Music City because of big studios or flashy labels. It became Music City because of the quiet, relentless work of songwriters and publishers who believed in the power of a well-written song-and were willing to wait for it to pay off.

What was the standard royalty split between songwriters and publishers in Nashville during the 1970s?

The standard split was 50/50 on performance royalties, but publishers kept 100% of mechanical royalties (8 cents per record sold in 1978). Writers typically signed away 50% ownership of the copyright in exchange for administrative support, advances, and promotion. This meant the publisher controlled the song’s licensing, publishing, and royalty collection, while the writer received half of the performance income after mechanicals were deducted.

How did songwriters submit their songs to Nashville publishers in the 1970s?

Songwriters had to physically visit Music Row offices, often daily, with handwritten lyrics and a demo tape recorded on a reel-to-reel machine. There were no online submissions or email pitches. Publishers required physical copies, and unsolicited demos had only a 12% chance of getting any response. Established writers with industry connections could get deals in 30-60 days; newcomers often waited 6 to 18 months.

Why did BMI play such a critical role in Nashville’s music publishing industry?

BMI (Broadcast Music, Inc.) was the primary organization responsible for tracking public performances of songs-on radio, TV, live venues, and jukeboxes-and paying royalties to publishers and songwriters. Without BMI, publishers couldn’t collect performance income. It was the central infrastructure connecting Nashville’s thousands of songs to revenue streams, especially as catalogs grew beyond manual tracking capacity.

How did Nashville’s publishing model differ from New York’s Brill Building system?

New York’s Brill Building operated like a factory: teams of professional songwriters, lyricists, and producers worked in close quarters, churning out pop songs on commission. Nashville, by contrast, relied on individual songwriters building personal relationships with publishers. Songs were often written alone, then pitched one by one. The focus was on emotional authenticity and artist fit-not formulaic production.

What happened to the publishing catalogs from the 1970s today?

Many 1970s Nashville catalogs have been acquired by major music publishers like Sony and Universal. These catalogs remain highly valuable because the songs continue to generate royalties from streaming, radio, and sync licensing. Analysts estimate Nashville-originated songs from that era now earn $85 million annually worldwide. Their value is rising as digital tracking improves, making it easier to collect royalties from global usage.