When Sly and the Family Stone took the stage at Woodstock in 1969, they didn’t just play music-they rewrote the rules. In front of 400,000 people, the band delivered a performance that was raw, electric, and unlike anything the crowd had ever seen. A Black frontman with a white saxophonist, a female trumpet player, a bassist who invented a new technique, and gospel-inspired harmonies layered over distorted organs. This wasn’t just a band. It was a revolution in sound and identity.

The Sound That Broke the Mold

Sly Stone didn’t just mix genres-he smashed them together. Before Sly and the Family Stone, soul music stuck to clear boundaries: smooth vocals, tight horns, steady rhythms. Funk was still emerging, mostly tied to James Brown’s rigid, percussive grooves. Rock was white, psychedelic, and often detached from Black musical traditions. Sly changed all that.

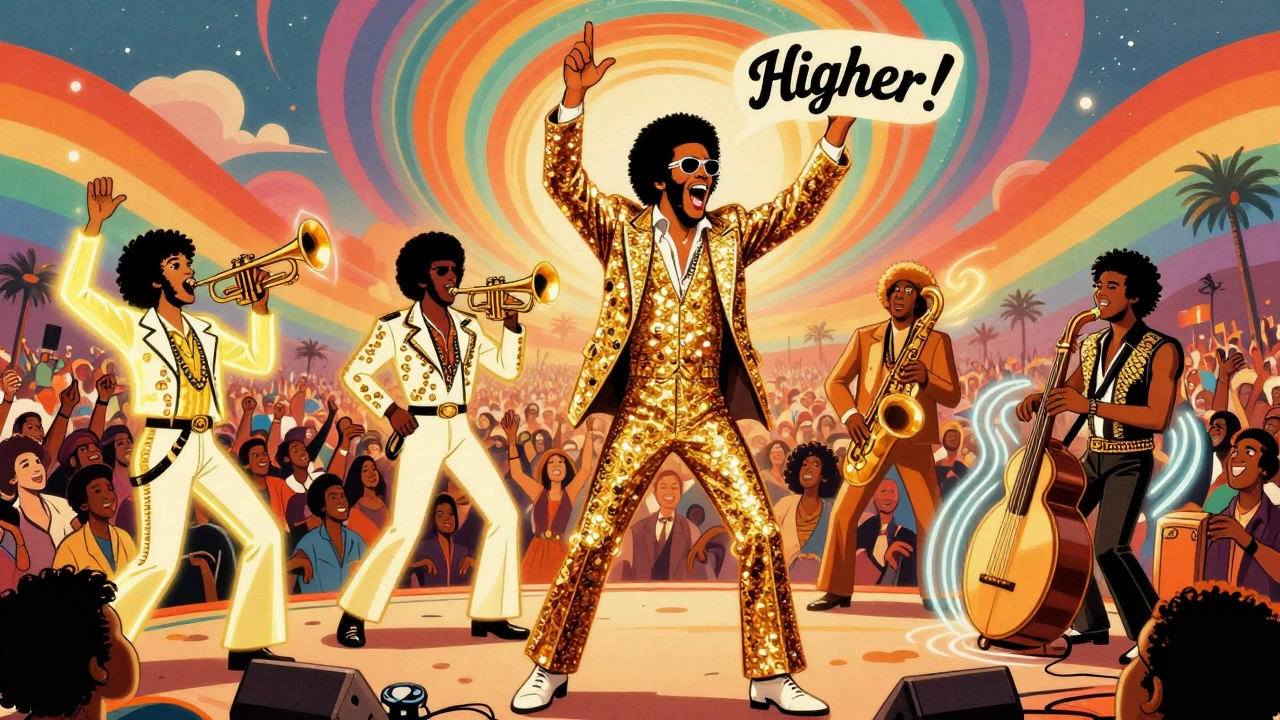

His music pulled from gospel choirs, rock guitar riffs, funk basslines, and psychedelic studio effects. The result? A sound that felt like a party in a protest march. Tracks like "Stand!" and "I Want to Take You Higher" didn’t just move your feet-they lifted your spirit. The call-and-response chants weren’t just catchy; they were communal. When Sly shouted "Higher!" the whole band and audience screamed back. That wasn’t production-it was connection.

What made it revolutionary wasn’t just the notes. It was the psychedelic soul-funk fusion. Horns slapped like a drum machine. Basslines slithered with slap technique, a method Larry Graham invented by accident while trying to play drums and bass at the same time. Sly’s organ wheezed like a distorted church bell. Guitar riffs bent like smoke. And behind it all? A rhythm so tight it felt like a heartbeat.

The Band That Refused to Be Classified

In 1967, when Sly and the Family Stone officially formed, they didn’t just break musical rules-they broke social ones. They were the first major American rock band with a racially and gender-integrated lineup. Black and white musicians. Men and women. Brothers and sisters. Sly’s sister Rose sang backup. His sister Vet sang with Little Sister, a gospel trio that added spiritual depth to songs like "Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin)." Cynthia Robinson, a Black woman, played trumpet like a rock star. Jerry Martini, a white man, blew saxophone with soul.

Compare them to other integrated bands of the time. Blood, Sweat & Tears had white members but no Black female musicians. Chicago Transit Authority had horns and complex arrangements, but none of the raw, joyful chaos Sly brought. Sly’s band didn’t just look different-they sounded different because they were different. Their unity wasn’t a gimmick. It was the foundation of their sound.

And it wasn’t just about race or gender. It was about class. Their music spoke to people who felt left out: Black youth in the inner city, white kids in the suburbs, women told to stay quiet. "Everyday People" became a #1 hit in 1968, not because it was flashy, but because it said something simple and true: "We are all the same." That message, wrapped in a funky groove, was dangerous in 1968. And it was unforgettable.

There’s a Riot Going On: The Dark Turn

By 1971, everything changed. The optimism of "Stand!" gave way to the heavy, murky sound of There’s a Riot Going On. The album was recorded in a haze of drugs, paranoia, and isolation. Sly Stone, once a charismatic bandleader, became a recluse. He recorded alone, layering vocals and instruments over weeks. The drums sounded muffled. The basslines were slow, heavy, almost drowning. The horns were buried. It wasn’t polished. It was broken.

And yet, it became a landmark. Billboard ranked it #1 on the R&B charts and #4 on the Pop charts. Critics called it the first true funk album that sounded like inner-city decay. The title track didn’t scream revolution-it whispered it. "Family Affair" followed in 1971 with a smooth, slow groove that became a radio staple. But behind the scenes, the band was falling apart.

Sly missed rehearsals. He showed up hours late. He stopped answering calls. The band kept playing, but the magic was fading. By 1973, they released Fresh, a final burst of brilliance with "Family Affair" and "Luv n’ Haight." But even then, Sly was checked out. He didn’t tour. He didn’t promote it. The fans noticed. The industry noticed. The magic was gone.

The Legacy That Won’t Die

Sly and the Family Stone didn’t last long. By the late 1970s, they were officially done. Epic Records tried to revive Sly’s career in 1979 with a compilation album called Ten Years Too Soon-but they replaced the original funk tracks with disco beats. It was a betrayal. Sly disappeared.

But his music? It never left.

Modern hip-hop producers sample Sly constantly. Dr. Dre used "Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin)" in "Nuthin’ But a ‘G’ Thang." Kanye West lifted the horn loop from "I Want to Take You Higher" for "Power." Prince, Prince, and D’Angelo all built their sounds on Sly’s foundation. Even today, artists like Bruno Mars and Anderson .Paak mix funk, soul, and rock the way Sly did-because he showed them how.

The band’s influence goes beyond rhythm. They proved that music could be political without being preachy. They showed that Black artists could own the rock stage. They proved that a woman’s trumpet could be the lead instrument in a rock band. They made integration sound natural, not forced.

In 1993, they were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. But the real honor? Every time a producer layers a bassline with a slap, every time a singer calls out and a crowd answers back, every time a band looks like the world instead of a narrow slice of it-they’re channeling Sly Stone.

Why This Still Matters Today

Look at today’s music. Artists blend genres without apology. Bands are diverse by default. Funk isn’t just a genre-it’s a feeling. That didn’t happen by accident. It happened because Sly and the Family Stone refused to play by the rules.

They didn’t wait for permission. They didn’t ask if it was "allowed." They just made the music they heard in their heads. And they made it loud enough for the whole world to hear.

That’s the real legacy. Not the hits. Not the awards. Not even the Woodstock performance. It’s this: music doesn’t have to fit in a box. It can be messy. It can be loud. It can be Black and white, male and female, soul and rock and funk all at once. And if you believe that, then you’re already listening to Sly Stone.