Where Grunge Was Born: The Venues That Made Seattle Sound Like Thunder

If you want to understand why grunge sounded the way it did-raw, loud, and full of anger-you don’t just listen to the albums. You walk into the rooms where it happened. The sticky floors. The broken amps. The walls that absorbed sweat, smoke, and screaming guitars. These weren’t fancy concert halls. They were dirty, cramped, and barely held together. And that’s exactly why they worked.

Seattle in the early 1990s wasn’t just a city. It was a pressure cooker. Bands like Nirvana, Pearl Jam, Soundgarden, and Alice in Chains didn’t start in studios. They started in basements, dive bars, and converted storefronts. The sound wasn’t polished. It was real. And it was shaped by the places they played.

The Central Saloon: The Birthplace of Grunge

At 312 1st Ave S, in the heart of Pioneer Square, sits the Central Saloon. Opened in 1892, it’s older than the city’s modern identity. By the 1980s, it was just another bar with a stage in the back. But in 1986, two Sub Pop Records founders, Bruce Pavitt and Jonathan Poneman, walked in and saw a band nobody had heard of: Nirvana. They played a set that was messy, fast, and strangely magnetic. That night, grunge got its first real spotlight.

The room holds only 300 people. The ceiling is low. The sound bounces off old brick walls that haven’t been touched in over a century. No sound engineers fixed the acoustics. No one tried to make it perfect. And that’s why it sounded so real. Bands didn’t need fancy gear. They just needed to play loud enough to be heard over the crowd. That’s where the distortion came from-not pedals, but space.

Today, it’s still there. Same barstools. Same sticky floors. Same sign out front. People still come to sit where Kurt Cobain once stood. One review from 2023 says it best: “Stepped into music history. Nothing changed. That’s the point.”

The Crocodile Café: The Secret Stage

When Nirvana’s Nevermind hit number one in January 1992, the band was already a global phenomenon. But in October 1992, just three months before the album exploded, they played a secret show at the Crocodile Café. No announcements. No tickets. Just a flyer taped to a phone pole. The room? About 1,200 square feet. The crowd? Around 150 people. No one knew it would become legend.

The Crocodile opened in 1991 in Belltown, a neighborhood still rough around the edges. It didn’t have a fancy sound system. It didn’t have reserved seating. It had a stage that creaked and a bar that never closed. Bands like Mudhoney, Pearl Jam, and Soundgarden played there constantly. It was the place where you could see a future superstar before they had a record deal.

The original Crocodile closed during the pandemic. But in 2021, it reopened two blocks away-with upgraded sound, better lighting, and a new owner who made sure to keep the old posters, the original stage floorboards, and even the same beer taps. If you visit today, you can still feel the weight of that 1992 show in the air. One fan wrote: “You can still feel the ghosts of Nirvana’s secret show in this room.”

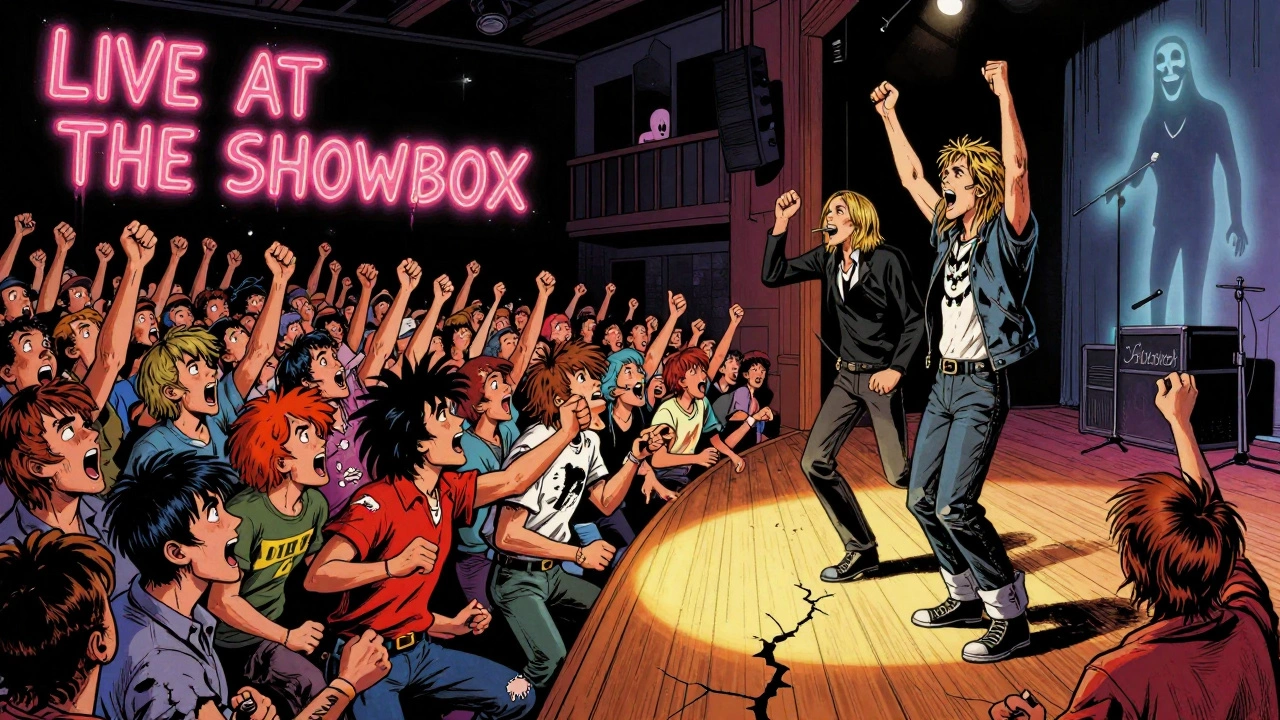

The Showbox: Where Bands Fought to Save Their Home

The Showbox opened in 1939 as a jazz club. By the 1990s, it was a grunge fortress. With room for 1,000 people, it was one of the few venues big enough to handle the crowds that started showing up after Nevermind. But it wasn’t just about size. It was about identity.

In 2019, developers wanted to tear it down and build condos. The response wasn’t quiet. Members of Pearl Jam, Soundgarden, and Nirvana’s surviving members signed petitions. Fans organized rallies. Local politicians stepped in. The Showbox was declared a City of Seattle Landmark. That’s rare for a music venue. Even the Paramount Theatre didn’t get that kind of protection until later.

Why did they fight so hard? Because the Showbox wasn’t just a building. It was where Soundgarden recorded live tracks that ended up on Superunknown. Where Alice in Chains played their first major Seattle show after signing with Columbia. Where the crowd didn’t just watch-they screamed back. The walls still hold the scars of those nights. And now, they’re legally protected.

The Paramount Theatre: The Stage That Was Recorded

Most grunge shows were loud, chaotic, and fleeting. But on Halloween night, 1991, Nirvana played at the Paramount Theatre-and someone hit record.

That show happened just five weeks after Nevermind dropped. The band was still figuring out how to handle fame. The setlist included early versions of songs that would become classics. The crowd was wild. Kurt wore a dress. The band played with fury. The recording? It became Live at the Paramount, released officially in 2011.

The Paramount isn’t just a concert hall. It’s a museum of moments. Soundgarden recorded their own live album there in March 1992. Pearl Jam played a surprise show in 1993. Today, the theater still hosts big-name acts. But if you sit in the balcony, you’re sitting where Kurt Cobain stood. The stage hasn’t moved. The wood still creaks the same way. The theater spent $1.2 million in 2023 just to preserve that stage. Not for nostalgia. For truth.

El Corazón and Re-Bar: Where the Scene Grew Up

On October 22, 1990, a band called Mookie Blaylock played their first show at Off Ramp Café. They changed their name to Pearl Jam the next year. That place is now El Corazón. It moved in 2022 after rising rent forced them out of their original 1910 building. But the legacy stayed. Fans still come to the new location to say they were there when Pearl Jam began.

Re-Bar, a smaller club in Capitol Hill, was where things got wild. In 1991, Nirvana threw their Nevermind release party there. The band started a food fight. They threw pizza, soda, and napkins into the crowd. Security kicked them out. The next day, every local paper ran the story. That wasn’t just a party. It was a statement: This isn’t pop. This isn’t polished. This is messy, and we’re proud of it.

Today, the original Re-Bar is gone. The building was torn down. But the story lives on. People still talk about it like it was a religious event.

The Black Dog Forge: The Basement That Made the Sound

Most people don’t know about the Black Dog Forge. It wasn’t a venue. It was a basement. 30 feet by 30 feet. No windows. Just concrete, amps, and a few old couches. Soundgarden rehearsed there. Pearl Jam (as Mookie Blaylock) practiced there. Nirvana dropped by when they were in town.

That’s where the sound was forged. Not in a studio. Not on a stage. In a dark, damp room with no acoustics at all. That’s why the music sounded so heavy. The walls didn’t reflect sound-they absorbed it. The bands had to play louder to hear themselves. That’s where the crushing distortion came from. Not because they liked it. Because they had to.

The building is gone now. A parking lot sits where it once stood. But if you ask anyone who was there, they’ll tell you: that basement was the real birthplace of the sound.

What’s Left, and What’s Lost

Half of the major grunge venues from the 1990s are gone. The original Off Ramp Café? Demolished. Re-Bar? Gone. The original Crocodile? Moved. KCMU radio, which first played grunge on the airwaves, left its old building in 1999 and now broadcasts from Seattle Center as KEXP.

But the ones that remain? They’ve become sacred ground. The Central Saloon still has the same sign. The Showbox still has the same stage. The Paramount still has the same seats where Kurt sat before walking out to play.

And people still come. Not just fans. Musicians. Journalists. Even teenagers who weren’t born when Nirvana broke up. They come to touch the walls. To stand where the music happened. Because this isn’t just history. It’s the reason the sound still matters.

Why These Places Still Matter

Grunge didn’t become big because of marketing. It became big because it was real. And it was real because of the places it was played. No fancy lights. No VIP sections. No ticket scalpers. Just people, music, and a room that didn’t care if you were famous.

Today, you can go to MoPOP and see Kurt’s guitar. You can buy a Sub Pop hoodie at Easy Street Records. You can even stay in a hotel room themed after the label. But none of that compares to standing in the Central Saloon and hearing the same creak in the floorboards that Kurt heard.

These venues didn’t just host bands. They shaped them. The bad acoustics made the guitars feedback. The small rooms made the crowd louder than the amps. The lack of money meant no polish-just passion.

That’s why grunge still sounds alive. Not because of the songs. But because of the rooms where they were born.

What was the first grunge band to play at the Central Saloon?

Nirvana played their first Seattle show at the Central Saloon in 1986. That’s where Sub Pop founders Bruce Pavitt and Jonathan Poneman first saw them, leading to their first record deal. No other band had a bigger impact on the venue’s legacy.

Can you still visit the original Crocodile Café?

No, the original location closed during the pandemic. But the Crocodile reopened in 2021 two blocks away, with the same name, the same spirit, and many original artifacts-like the stage floor and posters from the 1990s. The new space is bigger and better-sounding, but it still honors its roots.

Why was the Showbox saved from demolition?

In 2019, developers planned to tear down the Showbox to build condos. Surviving members of Pearl Jam, Soundgarden, and Nirvana signed petitions. Fans flooded city council meetings. The city granted it landmark status, making it one of the few music venues in the U.S. legally protected from demolition. It’s now a symbol of how communities can fight to preserve cultural history.

Where did Nirvana record their famous 1991 concert?

Nirvana recorded their legendary Halloween 1991 show at the Paramount Theatre in Seattle. It was just five weeks after Nevermind was released. The performance was later officially released as Live at the Paramount in 2011. The stage and audience seating are still exactly as they were.

Is the Black Dog Forge still around?

No. The Black Dog Forge was a 30x30-foot basement in South Seattle where Soundgarden, Pearl Jam, and Nirvana rehearsed in the early 1990s. The building was demolished in the late 2000s. Today, it’s a parking lot. But musicians still talk about it as the birthplace of the grunge sound.

How many grunge venues from the 1990s still exist today?

About half of the major grunge-era venues still operate, though many have moved or been renovated. The Central Saloon, Showbox, Paramount Theatre, and the new Crocodile Café remain open. Others, like Re-Bar and the original Off Ramp Café, have been demolished or closed permanently.