Back in the 1990s, if you wanted to hear about a band before they hit the radio, you didn’t scroll through Spotify playlists or TikTok trends. You picked up a folded, photocopied zine from a record store shelf, or you read the weekly paper tucked under your arm on the bus. The real power behind breaking local bands wasn’t MTV or major labels-it was the regional press. Newspapers, alt-weeklies, and DIY zines from cities like Seattle, Minneapolis, Athens, and Austin didn’t just report on music-they built scenes, shaped tastes, and sent underground bands straight into the national spotlight.

How Local Papers Became the First Big Break

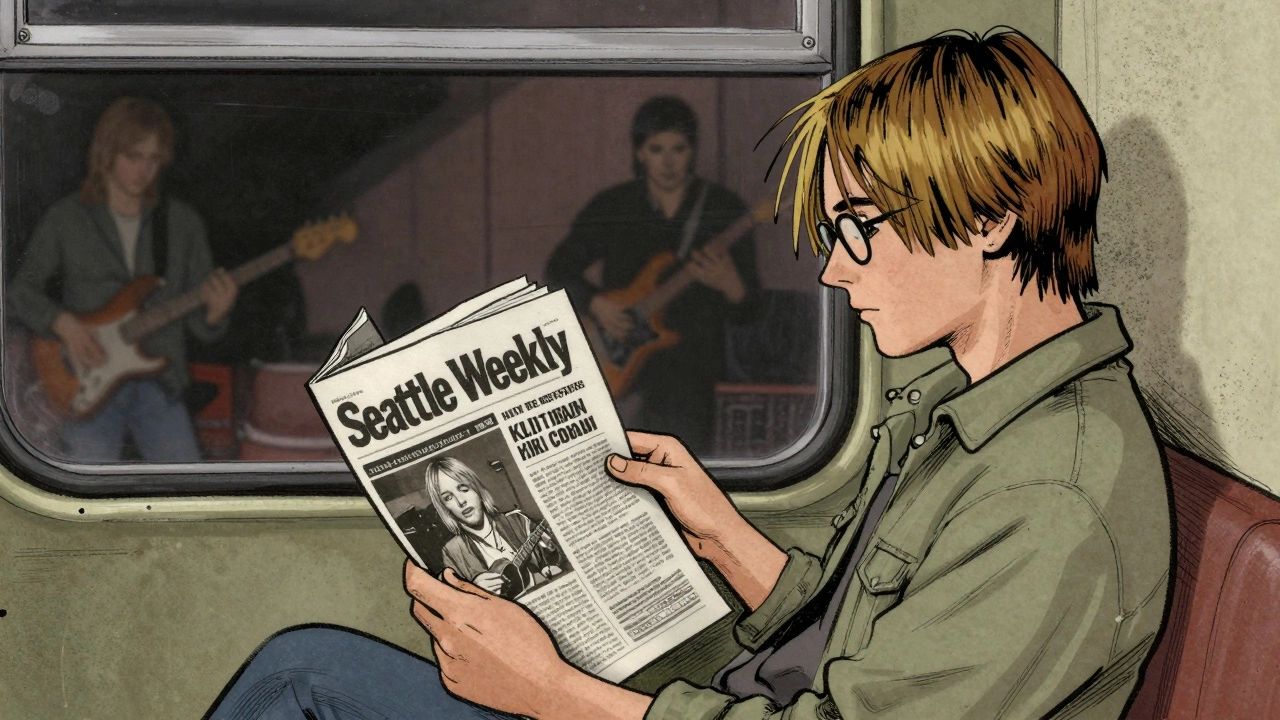

In 1991, a little-known band from Seattle called Nirvana played a show at the Vogue in downtown Seattle. The next day, the Seattle Weekly ran a two-page feature with a photo of Kurt Cobain leaning against a wall, looking tired but wired. The article didn’t call them "the next big thing." It just described their set: raw, loud, and weirdly magnetic. Within weeks, the piece was being passed around college radio stations, then picked up by The New York Times. That’s how it worked. Regional press didn’t chase trends-it caught them early.Other cities had their own versions. In Athens, Georgia, the Flagpole covered R.E.M. before they were signed, then turned its attention to the next wave: Neutral Milk Hotel, The B-52’s, and Pylon. In Minneapolis, the City Pages gave early ink to Soul Asylum and Prince’s side projects. These weren’t just event listings-they were investigative reports. Writers lived in the same neighborhoods as the bands. They went to basement shows, traded tapes, and wrote about what they felt, not what their editors told them to hype.

The Zine Revolution

Not every scene had a weekly paper. That’s where zines came in. Hand-stapled, typed on old typewriters, or printed on dot-matrix machines, zines like Maximum RocknRoll (San Francisco), Flipside (Los Angeles), and Chainsaw (Portland) became the backbone of underground music coverage. They didn’t have budgets, but they had credibility. A mention in Chainsaw could mean a band sold out a 200-capacity club the next month.These zines weren’t just reviews. They were oral histories. One 1993 issue of Flipside included a 12-page interview with the members of Fugazi, printed in full, unedited transcript form. No PR reps. No filters. Just the band talking about touring in vans, refusing to sign with major labels, and paying for their own records. That kind of honesty built trust. Readers didn’t just read-they believed.

The Technology That Didn’t Change the Game

You’d think the internet would’ve changed everything. But in the early 1990s, most regional outlets still used fax machines, landlines, and physical mail. Bands mailed promo tapes. Editors cut and pasted copy by hand. A feature might take three weeks from interview to print. That slowness was a feature, not a bug.When a band got coverage in the Chicago Reader or the Phoenix New Times, it didn’t go viral-it went deep. Readers saved the issues. They taped them to dorm walls. They passed them to friends. That slow burn meant the hype lasted. By the time a band made it to Rolling Stone or NME, they were already legends in their own cities. The regional press had done the hard work of proving they mattered.

The Bands That Got Their Start in Print

Look at the biggest names from the 1990s. Almost all of them got their first real press from local outlets:- Pavement-covered in East Bay Express before they even had a record deal

- Radiohead-first major U.S. feature in Austin Chronicle after their 1993 tour stop

- Beck-his first national buzz came from a 1994 L.A. Weekly piece on his lo-fi basement recordings

- The White Stripes-Detroit’s Metromix ran a cover story on them in 1999, calling them "the last great garage band" before they signed to V2 Records

These weren’t flukes. They were the result of consistent, local coverage. No one in New York or London knew who Beck was until the L.A. Weekly said he was worth listening to. No one in Europe cared about Radiohead until Austin’s music scene started talking about them.

The Decline and the Legacy

By the late 1990s, things started to shift. Advertising dollars dried up. Print runs shrank. Many alt-weeklies folded. The internet was coming, and with it, blogs and message boards. But the real loss wasn’t the paper-it was the relationship.Today, you can find a thousand blogs covering a new band the day they drop a single. But how many of them know the band’s history? How many have seen them play in a garage with no lights and a broken amp? The regional press of the 1990s didn’t just write about music-they lived it. They were fans first, journalists second.

That legacy didn’t disappear. It just moved. The best music podcasts today? They’re the new zines. The best indie YouTube channels? They’re the new alt-weeklies. The people who still go to basement shows and write about them? They’re carrying the torch.

Why It Still Matters

If you’re listening to music today, chances are you owe part of your taste to a 1990s regional paper. The bands you love didn’t rise because of algorithms. They rose because someone in a small office, in a city you’ve never visited, sat down and wrote: "This matters. Listen."That’s the power of local journalism. It doesn’t need millions of readers. It just needs one person who cares enough to write it down-and another who cares enough to read it.