When you think of reggae, you probably hear the slow, rolling beat of Bob Marley’s guitar. But look closer - the look is just as powerful as the sound. Reggae fashion isn’t just about what people wear. It’s a statement. A spiritual practice. A rebellion wrapped in red, green, and gold.

It started in the dusty yards of Trenchtown, Kingston, in the late 1960s. Not in fashion studios or runway shows, but in dancehalls where sound systems blasted out new music and people dressed to feel free. Clothes were loose, handmade, and colorful. Not because it was trendy, but because it was necessary. In a country still shaking off colonial rule, fashion became a way to say: we are not who they say we are.

The Colors That Carried a Movement

The red, green, and gold you see on shirts, hats, and bracelets isn’t random. It comes from the Ethiopian flag - the symbol of Black liberation. Red stands for the blood of those lost in the struggle. Green for the land of Africa, the ancestral home many Rastafarians believe they were taken from. Gold? That’s the wealth of Ethiopia’s emperors, especially Haile Selassie, whom Rastafarians see as a divine figure.

These colors didn’t stay on flags. They spread across everyday wear. In the 1970s, Jamaicans took plain white mesh marinas - the kind of under-shirts worn in Europe - and dyed them in those three colors. By the 1990s, dancehall stars like Spragga Benz and Buju Banton made them iconic. You’d see them in music videos, at parties, on the streets. Wearing them wasn’t a fashion choice. It was a declaration.

Dreadlocks, Tam Hats, and the Power of Comfort

Dreadlocks aren’t just hair. They’re a covenant. A sign of the Nazarite vow from the Bible, embraced by Rastafarians as a rejection of Babylon’s standards - the system of oppression, materialism, and conformity. But dreadlocks need care. That’s where the knitted tam comes in.

The tam - a crocheted hat, often in those same red, green, and gold stripes - wasn’t designed for style. It was made to protect. To shield the locks from wind, sun, and sweat. But over time, it became a symbol. Bob Marley wore one constantly. So did Peter Tosh. Today, if you see someone in a tam, you know they’re not just dressed up. They’re dressed in identity.

And the rest of the outfit? Always loose. Baggy pants. Oversized t-shirts. Flowing skirts. Nothing tight. Nothing restrictive. Because reggae fashion is built on freedom - freedom to move, to dance, to pray, to breathe. You don’t wear reggae style to impress. You wear it to feel right.

From the Streets to the Runway

For decades, reggae fashion stayed in Jamaica. Outside, people saw the music, not the clothes. But that changed. In the 2010s, designers started looking closer. Wales Bonner, a British designer with Jamaican roots, began weaving reggae’s spirit into her collections. She used sun-bleached denim. She stitched hand-dyed fabrics made by Jamaican women. She put tams on Paris runways. Not as costumes. As art.

Then came Theophilio, a Jamaican-American designer whose 2023 collection featured oversized mesh marinas, lion motifs, and beaded necklaces made in Kingston. His pieces weren’t inspired by reggae - they were made with reggae. He worked directly with local artisans. That’s the difference between appropriation and respect.

According to WGSN’s 2024 trend report, 23% of major fashion brands included reggae-inspired colors and silhouettes in their spring/summer lines. That’s up from just 6% in 2020. It’s not a fad. It’s a shift. People are tired of generic streetwear. They want meaning.

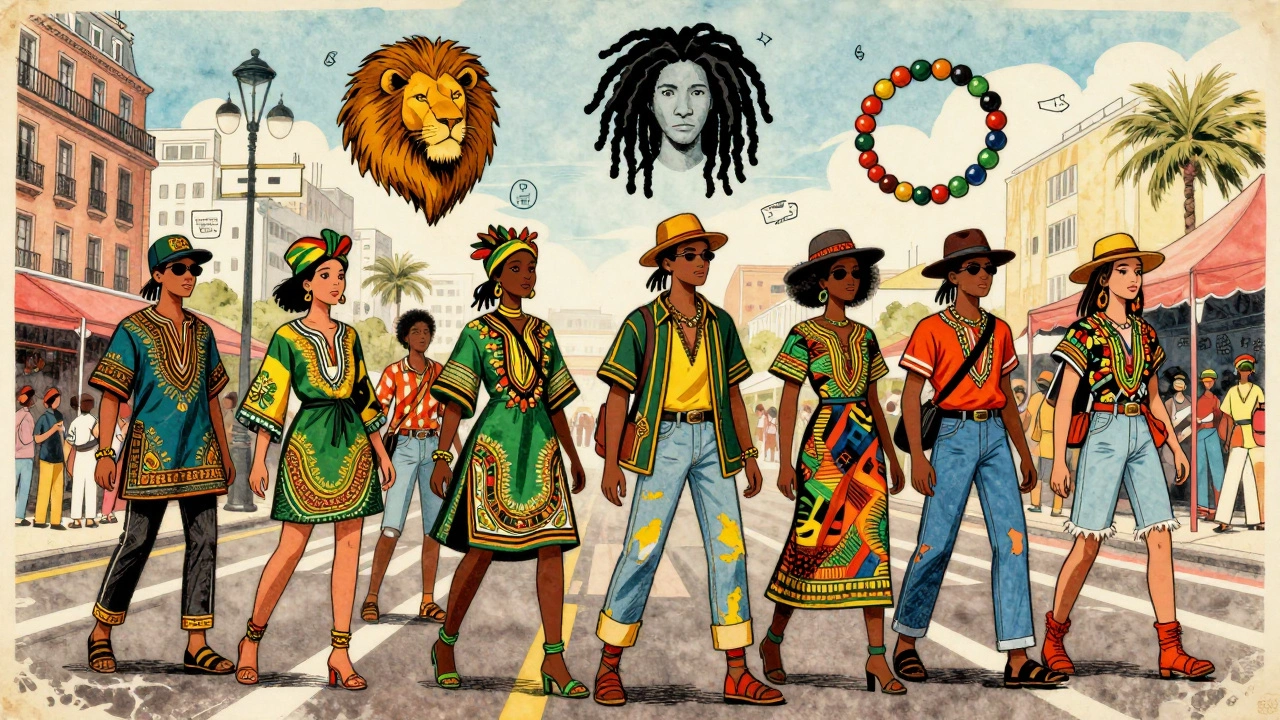

The Global Pulse: Social Media and Festivals

Instagram has over 4.7 million posts tagged #ReggaeFashion and #RastaStyle. TikTok has a creator named @ReggaeStyleGuide with 1.2 million followers. His videos - how to tie a tam, how to layer mesh marinas, where to find authentic beads - have been viewed over 85 million times. Young people aren’t just wearing the style. They’re learning its history.

Festivals are where it all comes alive. San Diego Bayfest draws 15,000 people every year. Not just for the music, but for the fashion. You’ll see elders in hand-sewn dashikis, teens in dyed denim, couples matching in red and gold. It’s not cosplay. It’s communion.

Statista reports that reggae-influenced fashion now makes up 8% of the global streetwear market - a $2.3 billion industry. But money isn’t the point. The real value is in connection.

The Archive and the Fight for Respect

In 2023, the University of the West Indies launched the Reggae Fashion Archive. It holds over 1,200 garments, photos, and oral histories. This isn’t just a museum. It’s a correction. For too long, global fashion history ignored Jamaica. Now, it’s being written into the record.

But there’s a dark side. In 2025, the Jamaica Intellectual Property Office recorded 42 cases of companies outside Jamaica trademarking Rastafarian symbols - the Lion of Judah, the colors, even the word “Rasta.” Some brands slap a lion on a hoodie and call it “vibes.” No context. No credit. No care.

Dr. Carolyn Cooper, a leading Jamaican cultural scholar, puts it plainly: “When you take the symbols without the story, you erase the revolution.”

That’s why the most important trend today isn’t the color palette or the loose fit. It’s the rise of collaboration. 67% of reggae-inspired collections in 2025 were made with direct input from Jamaican cultural experts. That’s progress. That’s respect.

Why It Still Matters

Reggae fashion didn’t become global because it looked cool. It became global because it carried truth. It was born in poverty, shaped by faith, and fueled by resistance. Every mesh marina, every tam, every beaded bracelet tells a story: we survived. We kept our culture. We didn’t ask for permission.

Today, you can buy a reggae-inspired hoodie in Berlin, Tokyo, or Toronto. But if you don’t know why the colors are red, green, and gold - if you don’t know who Bob Marley was fighting for - then you’re just wearing a pattern.

Real reggae fashion isn’t about trends. It’s about memory. About honoring those who wore their beliefs on their sleeves - literally. And if you choose to wear it? Wear it with understanding. Wear it with reverence. Because this style didn’t just come from Jamaica.

It came from struggle. And it still carries that weight.