Back in the 1970s, if you wanted to hear Led Zeppelin in Germany or Pink Floyd in Japan, you didn’t stream it. You bought a vinyl record-probably with a different cover, different track order, and sometimes even a different label name than the one on your home shelf. That was the world of international licensing deals, the quiet engine behind the global explosion of rock, funk, disco, and punk. Record labels didn’t just sell music; they built legal maps of the world, carving up territories like colonial powers dividing continents. And for the first time, American and British bands were reaching audiences far beyond their own borders-not because of radio waves, but because of contracts.

The Mechanics of a 1970s Licensing Deal

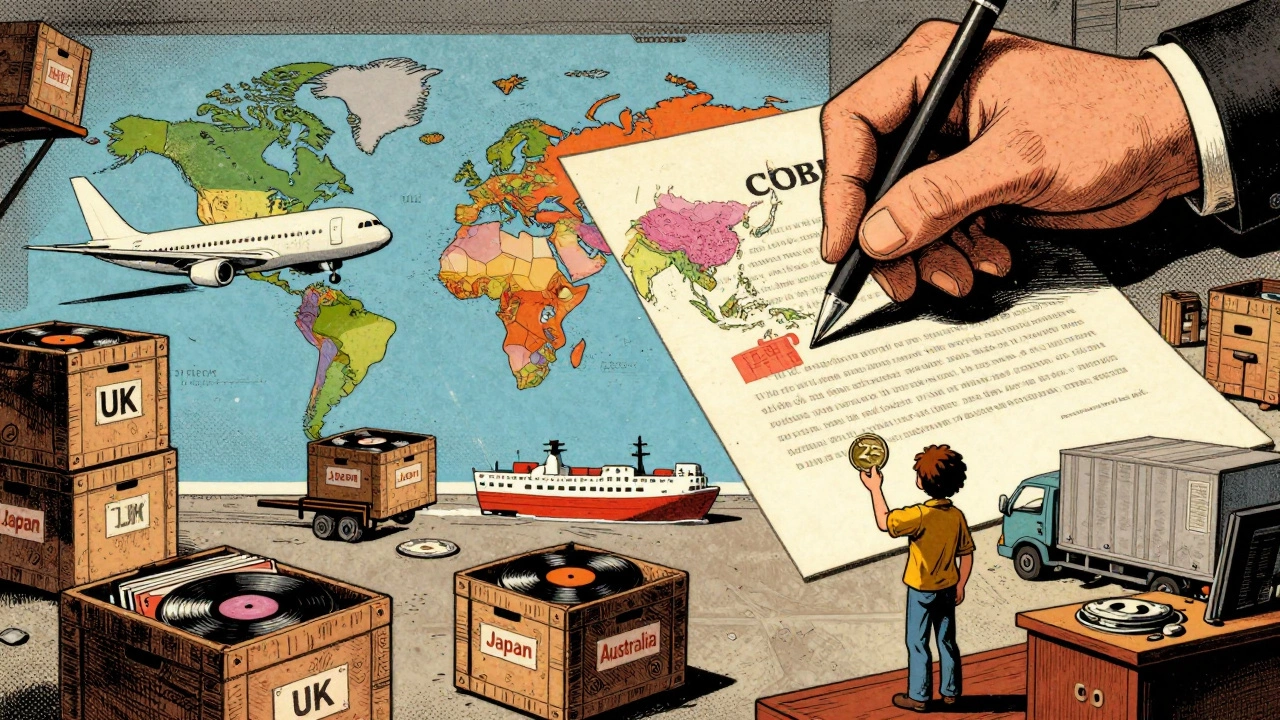

A licensing deal wasn’t a handshake. It was a 20-page legal document, typed on thick paper, signed by men in suits who rarely met the artists. The parent label-say, Atlantic Records in New York-would grant rights to a foreign company, like EMI in London or PolyGram in the Netherlands, to press, distribute, and sell their recordings in a specific region. The original label kept copyright. The foreign partner paid a royalty, usually 5% to 15% of wholesale price, and handled everything else: manufacturing, marketing, shipping, and even translating liner notes. The territory definitions were precise. The UK deal might include Canada and Australia. Germany might be separate from Austria. Japan was its own goldmine-American labels fought over it fiercely. A band like The Rolling Stones could have their album released by Decca in the UK, Atlantic in the US, and EMI in Australia, each with slightly different artwork. Fans didn’t care. They just wanted the music.Who Controlled the World?

By the mid-1970s, five giants ruled the global music business: CBS, EMI, Warner Communications, PolyGram, and MCA. These weren’t just labels-they were corporate empires. Warner Communications didn’t just own Warner Bros. Records. It also owned Elektra and Atlantic. In 1970, they merged their distribution arms into WEA (Warner-Elektra-Atlantic), creating a single powerhouse that handled international deals for all three. By 1975, WEA was pulling in over $18 million a year from overseas sales alone. PolyGram, formed in 1972 from the merger of Philips’ Polydor and Phonogram, became Europe’s most efficient distributor. They could sign one deal and push records across 15 countries at once. Meanwhile, EMI, the British giant, held tight control over Commonwealth territories and used its deep ties to London’s songwriting scene to repackage American hits for British audiences. When Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon blew up in 1973, it was EMI’s Harvest label in the UK and Capitol Records in the US-both under licensing agreements-that made it a worldwide phenomenon.Artists Got Paid-But Not Much

Most artists didn’t negotiate these deals. They signed with a label, and the label handled the rest. Royalties were low. A typical contract gave the artist 5% to 10% of wholesale revenue-meaning if a record sold for $5, the artist made about 25 to 50 cents per copy. Advances were rare for newcomers, but by 1979, top acts like Fleetwood Mac or David Bowie were getting $100,000 to $150,000 upfront. Adjusted for inflation, that’s nearly $1 million today. And here’s the catch: those advances had to be paid back before the artist saw another cent. Recording costs, tour support, even the cost of the album cover? All deducted from the artist’s share. Meanwhile, labels kept 85% of the revenue-and in many cases, they didn’t even tell the artist how many records were sold overseas. The contracts were opaque. As legal scholar Rebecca Tushnet pointed out, many deals buried clauses that slashed royalties for new formats like cassette tapes and, later, CDs. When the CD boom hit in the 1980s, artists were caught off guard. The system they’d signed onto in the 1970s didn’t account for digital reproduction.

American vs. British Styles

The American and British music industries operated differently. In the US, labels like Atlantic and Elektra hunted for raw talent-bands playing in basements, clubs, and garages. Ahmet Ertegun at Atlantic signed Led Zeppelin after hearing a demo. He didn’t care if they were unknown. He believed in the music. In the UK, it was more structured. Labels like Decca and EMI worked with managers who had already polished artists. Cliff Richard, Marty Wilde, and The Hollies were built by managers before labels even got involved. British labels also loved re-recording American hits with local singers. But by the mid-70s, that was changing. EMI’s Harvest label signed Pink Floyd and David Bowie-not because they were polished, but because they were original. It was a shift toward the American model. The hybrid model emerged with Casablanca Records. Founded by Neil Bogart in 1973, it was independent in spirit but used Warner Bros.’ global distribution. When Disco exploded, Casablanca’s artists-Kiss, Donna Summer, The Village People-sold millions overseas. By 1977, PolyGram bought half the company. It was the perfect marriage: creative freedom on one side, global reach on the other.The Flip Side: When Deals Broke Down

Not every deal worked. When the Sex Pistols appeared on British TV in 1976, swearing live on air, A&M Records panicked. They offered Richard Branson $75,000 to cancel the contract. Branson took it. Virgin Records signed the band instead. A&M lost a cultural moment. Virgin, a tiny label with no international network, had to scramble. But they licensed the Sex Pistols’ debut to EMI in the UK and Warner in the US. The album, Never Mind the Bollocks, became a global sensation-proof that nimble independents could outmaneuver giants. Smaller labels struggled. Buddah Records, once a hitmaker with The 5th Dimension and Neil Diamond, went bankrupt in 1976 after Neil Bogart left to focus on Casablanca. Without his drive and connections, their international deals collapsed. Meanwhile, Island Records’ Chris Blackwell built his label by licensing Millie Small’s “My Boy Lollipop” to Philips in the UK and handling US distribution himself. The confusion was real-fans in different countries bought different versions of the same song. But Blackwell didn’t care. He was building something new.