Before reggae hit the mainstream, rock music had a predictable beat: kick on one, snare on three, steady drive. Then, in the late 1960s, something shifted. A new rhythm slipped in - laid-back, off-kilter, with a pulse that felt like it was swaying on a Jamaican porch. It wasn’t just a new sound. It rewired how rock musicians thought about time, space, and feeling.

The First Crack in the Wall: The Beatles and 'Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da'

It started quietly. In 1968, The Beatles released "Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da," a song that sounded like a sunny Caribbean vacation wrapped in pop. The guitar chucks on the offbeat. The bass moves like it’s dancing, not walking. The drums skip the first beat. It wasn’t a full reggae song - but it was the first time the biggest rock band on Earth openly borrowed from Jamaica’s sound. Critics called it gimmicky. Fans shrugged. But inside recording studios, musicians took notice. If The Beatles could do it, maybe it wasn’t just a novelty. Maybe it was a door.Eric Clapton and the Moment Reggae Went Mainstream

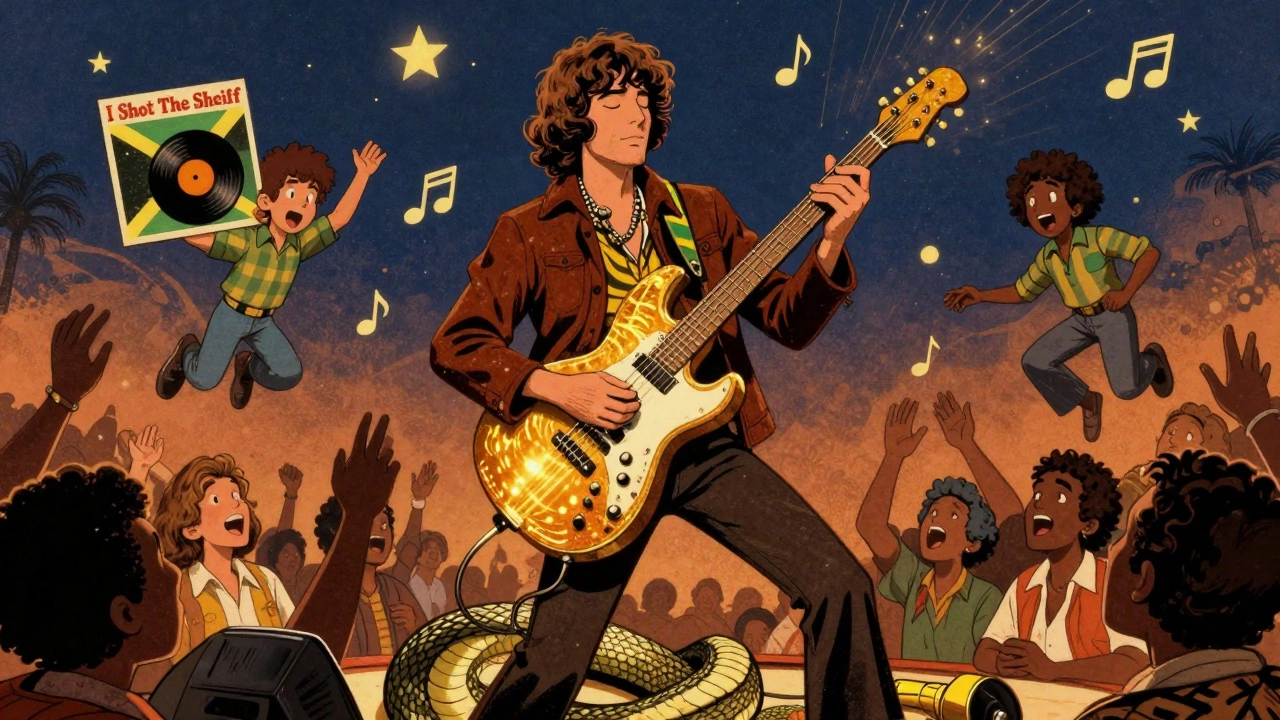

By 1974, reggae had found its rock ambassador. Eric Clapton, struggling to find direction after the breakup of Cream, recorded a cover of Bob Marley’s "I Shot The Sheriff." He didn’t just play it. He understood it. He slowed the tempo. He let the guitar breathe. He let the bass carry the melody. The song hit #1 in the U.S. Overnight, reggae wasn’t just a niche sound - it was a chart-topper. Radio stations that had never played a Jamaican artist suddenly spun it. Teenagers who didn’t know where Jamaica was started asking about "the one drop." Clapton didn’t just cover a song. He translated a culture for millions.The Rolling Stones, The Eagles, and the Art of Borrowing

The Rolling Stones didn’t just dabble - they went to the source. In 1973, they flew to Kingston, Jamaica, and recorded parts of "Goats Head Soup" at Dynamic Sound Studio. They covered "Cherry Oh Baby," a song by Eric Donaldson, and made it their own. But it wasn’t just about rhythm. It was about attitude. The Stones’ version felt loose, almost lazy - a far cry from their earlier blues-rock fire. Meanwhile, The Eagles were working on "Hotel California." Their original working title? "Mexican Reggae." The opening riff, with its slow, sliding groove, wasn’t meant to sound like Mexico. It was meant to sound like Kingston. The song’s moody, hypnotic feel came from reggae’s ability to stretch time - letting silence breathe, letting the bass hold the weight. It became one of the best-selling rock albums of all time, and reggae’s ghost was in every note.

The Skank, the One Drop, and the Bass That Changed Everything

Rock had always been about power. Reggae was about precision. The difference? The skank. That’s the guitar or keyboard chop on the offbeat - the "and" of the beat, not the "one." Rock guitarists had to relearn their hands. They used to strum down on every beat. Now, they had to skip the downbeat and land on the upstroke. It felt unnatural. Andy Summers of The Police spent months practicing it. He’d play along to reggae records, trying to match the feel. "It’s like your fingers are trying to walk backward," he once said. Then there was the one drop. In rock, the kick drum hits on beat one. In reggae, it hits on beat three. The snare taps lightly on two and four. The result? A loping, floating rhythm that made you sway instead of stomp. Stewart Copeland mastered it for "Roxanne." He didn’t just play the pattern - he made it feel like the whole room was breathing with him. But the biggest change was in the bass. Rock bassists played root notes - simple, grounding. Reggae bassists turned the bass into a lead instrument. It danced. It sang. It told stories. Sting’s bassline on "Roxanne" wasn’t just support - it was the melody. That shift changed how rock musicians thought about harmony. Bass wasn’t background anymore. It was the heartbeat.Punk, Reggae, and the Unlikely Alliance

In London, 1977, something unexpected happened. Punk was exploding - fast, angry, raw. But at the Roxy Club, a Jamaican DJ named Don Letts played reggae between sets. The kids didn’t just listen. They got it. The same people who screamed about unemployment and police brutality found the same rage in reggae’s lyrics. The Clash covered Junior Murvin’s "Police and Thieves." They didn’t turn it into a punk anthem. They kept the reggae groove, added distortion, and let the message stay sharp. It wasn’t appropriation - it was alliance. Punk gave reggae a stage. Reggae gave punk depth. This wasn’t just musical. It was political. In Britain, the Windrush generation had brought Caribbean culture to working-class neighborhoods. Reggae spoke to the kids who felt ignored. The Clash didn’t just borrow a rhythm - they borrowed a struggle. And when they did, they made sure the original writers got paid.

The Rise of Kali Reggae and the California Sound

By the late 1980s, a new wave emerged in Southern California. Bands like Sublime, Slightly Stoopid, and Rebelution didn’t just mix reggae and rock. They mixed it with punk, ska, and hip-hop. They called it "Kali reggae" - a nod to the Hawaiian word for "freedom." Their sound wasn’t polished. It was beachside, sunburnt, and real. Sublime’s 1996 self-titled album sold over five million copies. Fans didn’t care if it was "pure" reggae. They cared if it felt true. The band’s frontman, Bradley Nowell, grew up in Long Beach. He listened to Bob Marley and Black Flag in the same room. That’s the beauty of this fusion - it didn’t need permission. It just needed authenticity.What Worked - and What Didn’t

Not every attempt stuck. Some bands slapped a reggae beat under a rock song and called it done. The result? Flat, lifeless. Reggae doesn’t work as a gimmick. It needs space. It needs respect. UB40, a band from Birmingham, England, got it right. They didn’t try to sound Jamaican. They covered reggae songs - "Red Red Wine," "Kingston Town" - and paid the original writers. They let the music speak for itself. Their 1983 cover of "Red Red Wine" spent 31 weeks on the UK charts. In Jamaica? They were welcomed. Why? Because they honored the source. The Rolling Stones’ reggae experiments? Commercially successful. Culturally? Mixed. Some Jamaican fans called it superficial - like they were wearing a costume. The difference? The Stones didn’t live the culture. UB40 did. The Police? They studied. They recorded with Jamaican musicians. They let the rhythm lead.The Legacy: Reggae in Rock Today

Today, reggae rhythms are as much a part of rock as power chords. You hear it in SOJA’s anthems, in Stick Figure’s beachside grooves, in Hirie’s soulful ballads. Streaming data shows reggae-influenced rock tracks grew 28% year-over-year on Spotify in 2024. Coachella featured Ziggy Marley and The Offspring together in 2024 - a 90-minute set that blended reggae’s calm with punk’s fire. Over five million people watched live. YouTube tutorials on "how to play reggae guitar in rock" have over half a billion views. Ableton released "Reggae Groove Templates" in 2023 - downloaded 1.2 million times. New York University started a Reggae-Rock Ethnomusicology Program in 2021. This isn’t nostalgia. It’s evolution. Reggae didn’t just influence rock. It gave it a new soul. It taught rock how to breathe. How to feel. How to be slow without being weak. How to be quiet without being quiet. And that’s why, decades later, you still hear it - in a guitar chug, in a bassline that sings, in a drumbeat that makes you close your eyes and sway.Did Bob Marley directly influence rock musicians?

Yes. Bob Marley’s music and message reached rock artists directly. Eric Clapton’s 1974 cover of "I Shot The Sheriff" brought reggae into the mainstream rock charts. The Rolling Stones recorded in Jamaica and covered his contemporaries. The Police cited Marley’s rhythmic structure as a key influence. Marley’s global tours and media presence made him a cultural touchstone - not just for fans, but for fellow musicians seeking deeper meaning in their music.

What is the "skank" rhythm in reggae?

The "skank" is the signature offbeat guitar or keyboard chop in reggae - played on the "and" of each beat (the upstroke), not on the downbeat. It creates a syncopated, bouncy feel. Rock musicians like Andy Summers of The Police had to retrain their playing to nail this. Instead of strumming down on every beat, they learned to hit only the offbeats, which gave rock songs a new, laid-back groove.

Why did The Police succeed with reggae fusion?

The Police succeeded because they didn’t treat reggae as a trend. Drummer Stewart Copeland spent months mastering the "one drop" rhythm. Bassist Sting studied Jamaican basslines and made them melodic. Guitarist Andy Summers played sparse, atmospheric skanks instead of loud riffs. They recorded in Jamaica, respected the roots, and let the groove lead. Their album "Reggatta de Blanc" (1979) proved you could make reggae rock feel authentic - not just copied.

Did any rock bands fail at incorporating reggae?

Yes. Some bands added a reggae beat to a rock song without understanding its cultural or rhythmic foundation. The result often felt forced - like a cheap imitation. Critics point to early attempts by bands like The Rolling Stones as examples where the groove was there but the soul wasn’t. Jamaican fans criticized these efforts as superficial. The difference? Authentic fusion requires respect, study, and often collaboration with reggae musicians - not just a change in tempo.

Is reggae rock still popular today?

Absolutely. Bands like Sublime, Rebelution, SOJA, and Stick Figure continue to blend reggae with rock, punk, and hip-hop. In 2024, reggae-influenced rock tracks made up 7.3% of mainstream rock radio play in the U.S. Streaming platforms saw a 28% year-over-year growth in this genre. Festivals like Coachella feature reggae-rock acts alongside punk and indie bands. The fusion isn’t fading - it’s evolving.