The art world today doesn’t look like it did 50 years ago. Women aren’t just in the room anymore-they’re in the galleries, the museums, the textbooks, and the auction houses. But this wasn’t always true. In the 1970s, female artists didn’t wait for permission. They built their own spaces, used their own bodies as medium, and turned everyday objects into powerful statements. Their work didn’t just change art-it rewrote the rules.

They Didn’t Ask for a Seat. They Built a Table.

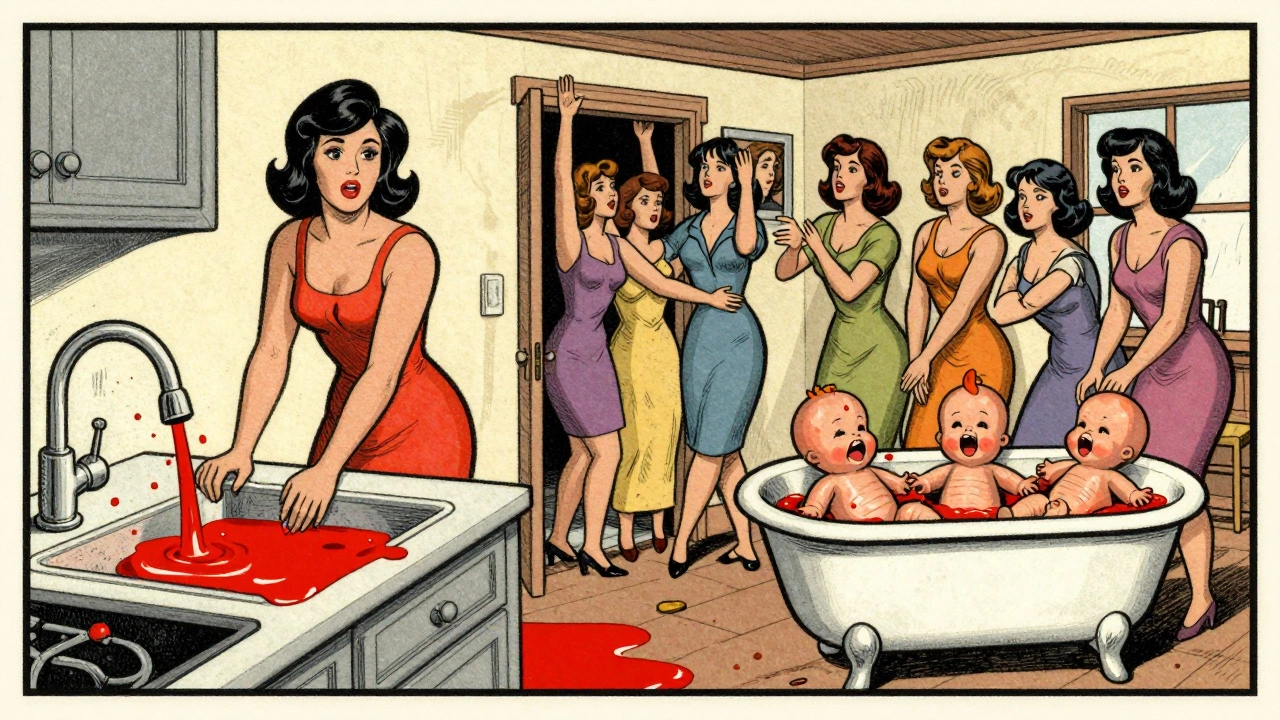

Judy Chicago didn’t just make art. She created a whole new system for making it. In 1970, she started the first feminist art program at Fresno State College. It wasn’t a class. It was a revolution. She gathered women who felt invisible in art schools and told them: your stories matter. Their first big project? Womanhouse a collaborative installation in a condemned Los Angeles house, transformed into rooms that explored domestic life through a feminist lens-kitchens with bleeding faucets, a bathtub filled with menstrual blood, a nursery made of baby dolls with screaming faces. It wasn’t pretty. It wasn’t polite. It was necessary.

That energy didn’t fade. Chicago kept going. In 1979, she finished The Dinner Party a 48-foot triangular table with 39 place settings, each honoring a historical woman-from Hypatia to Georgia O’Keeffe. The plates weren’t just decorative; they were vulvar forms, reimagining female anatomy as sacred, not shameful. Over 999 names of women were etched into the tile floor beneath. Today, it’s permanently displayed at the Brooklyn Museum. That’s not a footnote. That’s a cornerstone.

They Used the Media Against Itself

Barbara Kruger didn’t paint. She typed. In black-and-white photos of women’s faces, she slapped bold red text: "I shop therefore I am," "Your body is a battleground." She took the language of advertising-the kind that told women how to look, how to want, how to be-and twisted it into a mirror. Her work didn’t hang in galleries to be admired. It screamed at you from bus stops, magazines, and posters. She proved that text could be art. That politics could be aesthetic. That the billboard could be a canvas.

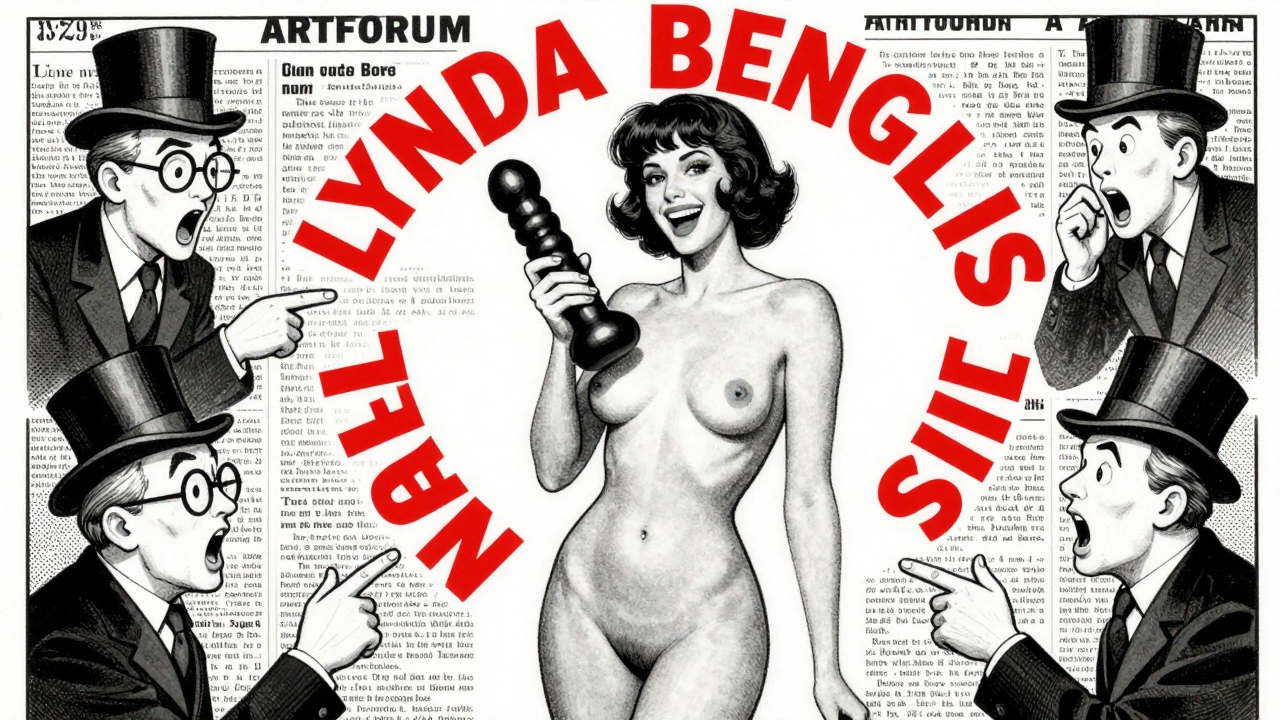

Lynda Benglis did something even more shocking. In 1974, she bought an ad in Artforum. It showed her naked, holding a large dildo, grinning. No caption. No context. Just her. The art world erupted. Critics called it vulgar. Men called it a joke. But Benglis wasn’t trying to shock for shock’s sake. She was calling out the hypocrisy: male artists got praised for raw, sexual work. Female artists? They were told to stay quiet. Her ad forced the art world to face its double standard. And it worked. Today, artists use mass media like Instagram, billboards, and memes the same way-because she showed them how.

They Made the Body the Canvas

Marina Abramović didn’t use paint. She used her own body as the material. In the 1970s, she did performances that left audiences breathless. In Rhythm 0 (1974), she stood still for six hours while viewers could use any of 72 objects on her-roses, scissors, a gun. One person shot her. Another cut her. She didn’t move. She didn’t scream. She just stood there. The piece wasn’t about pain. It was about power. Who holds it? Who takes it? Who lets it go?

Her work didn’t just push boundaries-it erased them. Today, performance art is everywhere. From Marina’s own MoMA retrospective in 2010 to contemporary artists like Tino Sehgal and Yoko Ono’s re-performances, the idea that art happens in real time, with real bodies, comes straight from her 1970s experiments. The body isn’t just a subject. It’s the medium.

They Reclaimed the Stereotype

Betye Saar didn’t wait for permission to speak about race or gender. She went straight to the source: junk drawers, thrift stores, and old advertisements. In 1972, she made The Liberation of Aunt Jemima a mixed-media assemblage: a mammy figure holding a rifle, standing beside a bottle of syrup, with a fist raised. Behind her, a photo of a Black soldier from World War II. The piece turned a racist caricature into a symbol of resistance. Angela Davis said it helped launch the Black women’s movement. That’s not hyperbole. That’s history.

Saar didn’t just make art. She built archives. She collected the trash the world threw away-minstrel masks, postcards, broken dolls-and turned them into monuments. Her method became a blueprint: take what was used to control you, and turn it into a weapon. Today, artists like Kara Walker and Mickalene Thomas use the same strategy. They don’t erase the past. They rewrite it.

They Photographed the Illusion

Cindy Sherman didn’t take portraits. She took identities. In the mid-70s, she started dressing up as different women: housewives, movie stars, clowns, victims. She didn’t hire models. She was always the subject. Her Untitled Film Stills (1977-1980) looked like scenes from B-movies-but they were never real. No movie. No script. Just her, in a wig, under a lamp, pretending.

She showed that femininity isn’t natural. It’s constructed. It’s performed. It’s bought, sold, and recycled. Her work didn’t just influence photography. It changed how we think about identity. Today, TikTok influencers, Instagram personas, and digital avatars all live in the world Sherman invented. She proved that the camera doesn’t capture truth-it creates illusions. And we’re still living inside them.

The Legacy Isn’t Just in Museums. It’s in the Rules.

Before the 1970s, women were invisible in art history. After them? They became the foundation. These artists didn’t just add women to the canon. They broke the canon and rebuilt it. They created institutions like Womanspace Gallery. They wrote manifestos. They taught classes. They published books. They turned art into activism.

Look at today’s art world. The rise of identity-based art. The explosion of performance. The dominance of photography. The way artists use social media like a protest sign. All of it traces back to these women. They didn’t just make art. They made space-for themselves, for others, for future generations.

Their work wasn’t about being "feminine." It was about being seen. And they refused to be quiet.

Why were 1970s feminist artists so radical?

They were radical because they refused to play by the rules of a system that excluded them. Art schools, galleries, and museums were dominated by men who decided what counted as "real" art. Women were pushed into crafts-needlework, ceramics-seen as "lesser." Feminist artists flipped that. They used performance, text, photography, and found objects to challenge the idea that art had to be painted on canvas by a man. They turned their exclusion into a method. That’s why their work felt so disruptive-it wasn’t just about content. It was about structure.

Did these artists only focus on gender?

No. While gender was central, many also tackled race, class, and sexuality. Betye Saar’s work connected feminism with Black liberation. Nancy Buchanan and Susan Singer explored class and labor. Lynda Benglis challenged how sexuality was portrayed in media. They didn’t see these issues as separate. They saw them as layered. Today’s intersectional art-work that addresses race, gender, and class together-directly builds on their approach.

How did these artists change how art is taught?

Before the 1970s, art education was mostly about technique: how to paint, sculpt, or draw like the old masters. Judy Chicago’s Feminist Art Program changed that. It taught students to think critically about who gets to make art, whose stories are told, and why. Students worked collaboratively. They made art about their own lives. They didn’t just learn skills-they learned how to question power. Today, nearly every art school includes critical theory, identity-based practices, and collaborative projects because of them.

Are these artists still relevant today?

More than ever. Cindy Sherman’s exploration of identity is echoed in every selfie and Instagram filter. Barbara Kruger’s text-based critiques are all over protest signs and memes. Marina Abramović’s performances inspire artists who use live streaming and VR. Even the rise of digital art and NFTs-where ownership, identity, and performance collide-has roots in their 1970s experiments. Their work wasn’t a trend. It was a framework.

Why isn’t this history taught more in schools?

Because the art world still struggles with its own biases. Major museums have only recently begun to acquire and display feminist art from the 1970s at the same scale as male artists. Textbooks still often skip over these artists or bury them in a footnote. But that’s changing. Institutions like the Brooklyn Museum, MoMA, and Tate Modern now have dedicated feminist art galleries. The resistance isn’t gone-but the visibility is growing.

What Comes Next?

The artists of the 1970s didn’t just open doors. They handed out the keys. Today’s artists-nonbinary, trans, Indigenous, global south-build on their work, not by copying it, but by expanding it. They use digital tools, social media, and global networks to ask new questions: Who gets to be seen? Who gets to be remembered? Who gets to decide what’s valuable?

The answer to those questions still starts with the women who refused to be silent.