By 1970, the planet was screaming. Rivers caught fire. Forests vanished under bulldozers. Pesticides poisoned the air. And somewhere between the smokestacks and the strip mines, musicians picked up their guitars and started singing about it.

When the Music Turned Green

The first Earth Day in April 1970 wasn’t just a protest-it was a cultural earthquake. Twenty million Americans took to the streets, schools, and parks to demand change. That same year, the Clean Air Act passed. The Environmental Protection Agency was born. And suddenly, music wasn’t just about love and rebellion anymore. It was about loss. Artists didn’t wait for permission. They didn’t need a grant or a nonprofit backing them. They just wrote. Joni Mitchell, Neil Young, John Prine, Cat Stevens-they turned their songs into warnings. Not vague poetry. Not just pretty pictures of trees. Real, specific, gut-punching lyrics that named names and pointed fingers. Joni Mitchell’s Big Yellow Taxi, released in September 1970, didn’t just mourn lost nature. It accused. “They took all the trees, put them in a tree museum / And charged all the people a dollar and a half just to see ’em.” That wasn’t metaphor. That was DDT. That was the chemical spray killing birds and poisoning soil. She didn’t say “pollution.” She named the poison. And she made you feel it.The Songs That Named the Crime

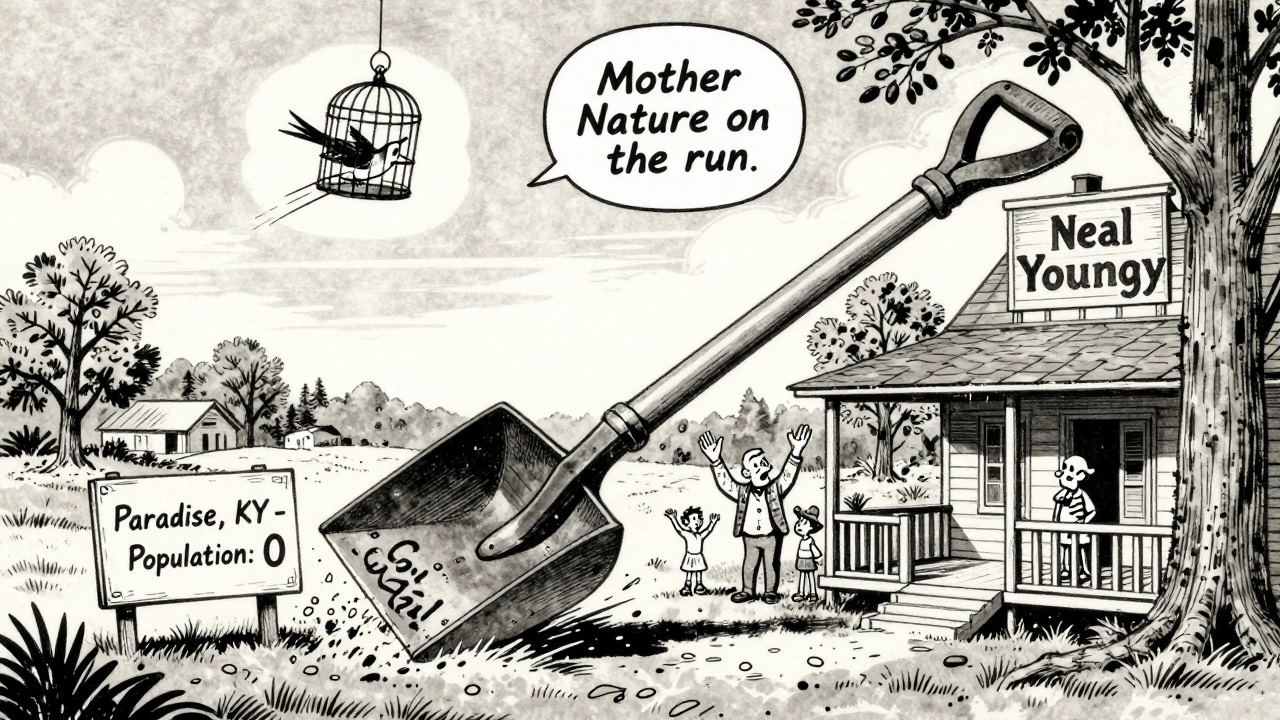

John Prine’s Paradise didn’t talk about nature in general. It talked about one place: Paradise, Kentucky. A town erased by coal mining. “Then the coal company came with the world’s largest shovel / And they tortured the timber and stripped all the land.” This wasn’t abstract environmentalism. It was a funeral for a community. Prine didn’t sing about saving the planet-he sang about losing a home. Neil Young’s After the Gold Rush was a haunting vision. “Look at Mother Nature on the run in the 1970s.” He didn’t say “climate change.” He didn’t need to. He painted a world unraveling. Decades later, he changed the lyric to “21st century” in concert. Not because the song aged poorly. Because it aged too well. Cat Stevens’ Where Do the Children Play? asked a question that still echoes: “How can the birds that are born to fly / Live in a wire cage and never have to die?” It wasn’t about saving birds. It was about what kind of world we were building for kids. A world of concrete, fences, and silence. Even the Eagles got in on it. The Last Resort told the story of America’s ecological theft-from the Pilgrims to the developers. It wasn’t a protest song. It was a historical record set to music.

What Made These Songs Different

Before the 1970s, nature in music was romantic. Think Beatles’ Mother Nature’s Son-sweet, gentle, safe. No threats. No consequences. Just a nice walk in the woods. The 1970s changed that. These songs weren’t about beauty. They were about loss. And they didn’t just describe the problem-they named the cause. Corporations. Government inaction. Consumerism. Industrial greed. Dr. Mark Pedelty, who wrote the book on ecomusicology, called it the first time musicians engaged with “ecological systems thinking.” Not just trees and rivers. But how they fit into a broken system. That’s what made these songs powerful. They didn’t ask you to love nature. They asked you to question why you were destroying it. And they worked. Joni Mitchell’s Big Yellow Taxi didn’t just chart-it stuck. The Counting Crows covered it in 1997. Billie Eilish sang it for Earth Day Live in 2021. Over 15 million people watched. That’s not nostalgia. That’s a message that still fits.The Blind Spots

But it wasn’t perfect. Most of these songs came from white, Western artists. Bob Marley’s Concrete Jungle was one of the few that spoke from a different reality-the concrete jungles of Kingston, Jamaica. Urban decay. Overcrowding. Pollution as a tool of neglect. That perspective was rare. Only 12% of environmental songs in the 1970s addressed global justice. The rest focused on American forests and rivers. The pollution in Bangladesh. The deforestation in the Amazon. The oil spills off Nigeria. Those stories didn’t make the charts. Critics like Greil Marcus called out the “vague pastoralism” in some of these songs. He had a point. Some lyrics were pretty but shallow. They mourned nature without naming the system that killed it. But even the imperfect songs mattered. Because they made people feel something. They made you sit still. Look out the window. Wonder if your town was next.