Before streaming, before CDs, before even cassette tapes, there were bootleg recordings-illegally made live concerts captured on hidden recorders and passed hand to hand like underground currency. These weren’t just bad copies. They were the only way fans got to hear their favorite bands play songs that never made it onto studio albums. A Led Zeppelin show in 1977 wasn’t just a concert-it was a once-in-a-lifetime event, and if you didn’t attend, your only shot at hearing it came through a bootleg. That’s the story behind the culture that turned unauthorized recordings into priceless artifacts.

How It All Started

The very first bootleg recording happened in 1901. Lionel Mapleson, the librarian at the Metropolitan Opera, slipped a small recording device into his coat and captured live performances on a Bettini cylinder recorder. No one asked for permission. No one cared. It was just a curious experiment. But it set a precedent: fans wanted access to something official releases didn’t offer. Fast forward to 1969. The world changed with the release of Great White Wonder. This wasn’t some dusty tape passed around in a basement. It was a full double LP, pressed in bulk, sold in underground record shops across the U.S. It featured unreleased Bob Dylan recordings-some studio outtakes, some live tracks. For the first time, bootlegs went from niche curiosity to mass-market phenomenon. The demand was so high that record stores couldn’t keep them in stock. This wasn’t just about music anymore. It was about control. Fans were tired of waiting for labels to release what they wanted, when they wanted it.Why Live Recordings Dominated the Market

About 80% of all bootlegs were live recordings. Why? Because live shows were where the magic happened. Studio albums were polished, edited, layered. Live performances were raw, unpredictable, and often better. A Led Zeppelin concert could stretch a three-minute song into ten, with Jimmy Page improvising solos no one had ever heard before. A Rolling Stones gig in 1969 had Mick Jagger screaming at the crowd like a man possessed. These moments didn’t exist anywhere else. The most famous bootleg of all time? Live R Than You’ll Ever Be. Recorded during the Stones’ 1969 American tour, it was pressed on plain white sleeves with a rubber stamp that read “Live R Than You’ll Ever Be.” No artist credit. No label. Just the music. It sold around 150,000 copies. That kind of demand scared the record company. Within a year, they rushed out their own official live album: Get Yer Ya-Ya’s Out!. The bootleg didn’t just feed the market-it forced the industry to respond.The Two Kinds of Bootlegs: Audience vs. Soundboard

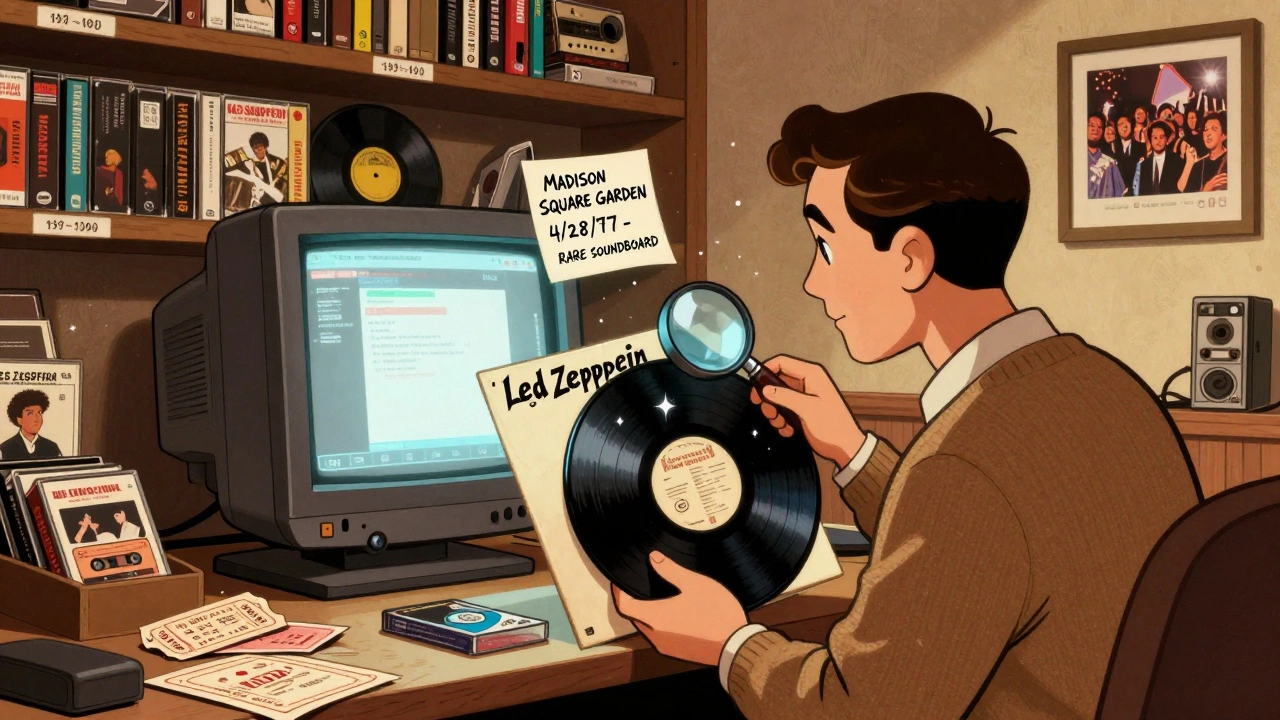

Not all bootlegs were created equal. There were two main types, and the difference was everything. First, audience recordings. These were made by fans with tiny recorders hidden in backpacks, jackets, or even shoes. The sound? Muffled. Drowned out by crowd noise. Sometimes you could barely hear the vocals. But they were everywhere. You could find them at concerts, record fairs, even gas stations. These were the common currency of bootleg culture. Then there were soundboard recordings. These came from the mixing console-the same feed the sound engineer used to balance the amps, mics, and monitors. These were pristine. Clear. Balanced. You could hear every guitar string, every kick drum hit. But getting one? Nearly impossible. You needed someone on the inside: a roadie, a technician, a stagehand. These were the holy grails. A single soundboard tape could sell for 300-400% more than an audience recording. Led Zeppelin’s Destroyer, a four-LP set of their 1977 Madison Square Garden show, was one of these. The audio was rough, but the setlist was legendary. People paid $150 for it in 1977. That’s over $750 today.

The Cult of the Collector

Collectors didn’t just want the music-they wanted the story. The packaging. The history. The Grateful Dead were the epicenter of this culture. The band didn’t just tolerate taping-they encouraged it. Deadheads, as fans called themselves, recorded over 14,500 unique shows. Each one was cataloged, labeled, traded. A bootleg wasn’t just a recording. It was a piece of a shared experience. Some bootlegs became legendary for their packaging. The Blind Faith album was pressed on recycled hardcover tour books. The Rolling Stones’ Live R Than You’ll Ever Be had handwritten track listings. These weren’t mass-produced. They were handmade. Each copy had slight variations-different ink, different paper, different stamps. Collectors spent years learning how to tell a first pressing from a third-generation copy. One Reddit user, who goes by TapeHoarder42, spent $300 in 1995 on a mint condition Bob Dylan Royal Albert Hall bootleg. When Columbia Records officially released it in 1998, its value dropped to zero. That’s the risk. The thrill. The gamble.From Underground to Official

The music industry didn’t fight bootlegs forever. It learned from them. Elton John’s 1970 FM radio broadcast was bootlegged under multiple titles. Fans loved it. So his label eventually released it officially as 17-11-70. Frank Zappa didn’t sue bootleggers-he outsmarted them. In 1992, he released Beat the Boots, remastering the exact bootleg recordings, copying their packaging, and selling them under his own name. The bootleggers had no chance. The biggest shift came with Bob Dylan. In 1991, he launched the Bootleg Series. Officially. With remastered audio, liner notes, unreleased tracks. Suddenly, the thing fans had been risking their money and time for was now available legally. The series now has 17 volumes. It didn’t kill bootlegs-it co-opted them.

The Digital Shift and the Vinyl Resurgence

The 2000s killed the physical bootleg market. Torrents, FTP servers, and file-sharing made tapes and CDs obsolete. You could download a full 1973 Pink Floyd show in seconds. But something strange happened. As digital files became endless, collectors started craving the physical. Original vinyl pressings of rare bootlegs-like the first pressing of Great White Wonder-now sell for over $5,000. Discogs reports a 200% spike in high-end bootleg sales between 2018 and 2023. Why? Because these aren’t just recordings. They’re artifacts. They’re history. The crackle of a 78 RPM disc. The smell of old vinyl. The handwritten track list on a white sleeve. These things can’t be replicated. Meanwhile, artists like KISS and Peter Gabriel began selling official “bootlegs”-soundboard-quality recordings sold at the merch table right after the show. The line between illegal and legal blurred. The culture didn’t die. It evolved.Why This Still Matters

Bootleg recordings weren’t just about breaking the rules. They were about preserving what mattered. Many official live albums are stitched together from multiple shows. A real bootleg? It’s one night. One performance. One moment in time. That’s irreplaceable. The people who collected these tapes weren’t thieves. They were archivists. They saved performances that labels ignored. They kept alive versions of songs that never made it to streaming services. They built communities around shared passion, not profit. Today, you can stream every officially released Led Zeppelin track. But if you want to hear the version where Robert Plant screams “I’m a king bee” into a feedback loop for five straight minutes? You still need a bootleg.Are bootleg recordings illegal?

Yes. Bootleg recordings are unauthorized and violate copyright law. However, enforcement has always been inconsistent. Many artists, like the Grateful Dead, openly allowed taping. Others, like Led Zeppelin, sued bootleggers but still inspired massive underground markets. The legal status hasn’t stopped the cultural value.

What’s the difference between a bootleg and a counterfeit?

A counterfeit tries to fool you into thinking it’s an official release-fake labels, fake artwork, fake catalog numbers. A bootleg is transparent. It doesn’t pretend to be official. It often has plain packaging, handwritten labels, or no label at all. Bootlegs sell because they offer unreleased content, not because they’re trying to trick you.

Why do collectors pay so much for low-quality bootlegs?

It’s not about sound quality-it’s about rarity and authenticity. A muddy audience recording of a legendary 1974 concert might be the only surviving version of a song the band never played again. Collectors value the historical snapshot, not the fidelity. A 1977 Led Zeppelin bootleg might sound terrible, but if it captures a rare setlist, it’s priceless.

Can you still find physical bootlegs today?

Yes, but they’re rare. Most physical bootlegs are now collector’s items sold through specialized forums, eBay, or record fairs. The market has shifted from mass distribution to high-end auctions. Vinyl pressings from the 1970s and 1980s are the most sought-after, with some selling for thousands of dollars. Digital bootlegs are far more common, but collectors still prize original pressings for their tactile history.

What artists are most bootlegged?

The top five most bootlegged artists are The Beatles, Led Zeppelin, The Rolling Stones, Bob Dylan, and Bruce Springsteen. Prince’s canceled The Black Album became one of the best-selling bootlegs ever, with over 500,000 unofficial copies circulating. The Grateful Dead hold the record for most recorded shows, with 14,566 distinct bootlegs cataloged by fans.

Did bootlegs ever help artists financially?

Indirectly, yes. Bootlegs proved there was demand for live recordings that labels ignored. The Rolling Stones’ Live R Than You’ll Ever Be led directly to their official live album. Elton John’s bootlegged radio broadcast became his official 17-11-70 release. Even Bob Dylan’s Bootleg Series was a direct response to decades of fan demand fueled by bootlegs. The underground market forced the industry to adapt.