Before auto-tune, before DAWs, before even MIDI - there was the arpeggiator. In the late 1970s, this simple circuit turned a single chord into a driving, pulsing rhythm. It didn’t need a programmer. It didn’t need a sequencer. You just held down a chord, and the machine did the rest. For musicians trying to keep up with the speed of disco, the complexity of prog rock, or the cold precision of new wave, the arpeggiator wasn’t just a tool - it was a lifeline.

The Sound That Changed Everything

Think of the opening of Blondie’s "Atomic" (1979). That bright, repeating pattern? It wasn’t played by hand. It came from a Roland Jupiter-4 a polyphonic analog synthesizer released in 1978 with one of the first built-in arpeggiators. One hand held the chord, the other added accents. No studio trickery. No multi-tracking. Just raw, analog rhythm. That’s how the arpeggiator changed the game. Before 1978, musicians like Tony Banks of Genesis spent hours manually playing arpeggios on keyboards, fingers flying, trying to mimic a machine. After 1978, machines could finally keep up with them.The ARP Quadra a four-section synthesizer with a polyphonic arpeggiator that could layer bass, strings, and lead lines simultaneously took it further. Unlike earlier monophonic synths, the Quadra let you play one chord and have four different arpeggiated parts respond - bassline, pad, melody, and harmony - all at once. It was like having four musicians in one box. Session players used it on records by Weather Report and Donna Summer’s producers, layering pulsing textures that felt alive, even if they were generated by circuits.

How It Actually Worked (And Why It Was Flawed)

Late 1970s arpeggiators weren’t digital. They ran on analog circuits powered by transistors and capacitors. That meant they didn’t have perfect timing. They had character. The Roland Jupiter-4 a polyphonic analog synthesizer released in 1978 with one of the first built-in arpeggiators had three modes: up, down, and up-down. You could set the range to one, two, or three octaves. Tempo synced to the synth’s internal clock - usually between 40 and 240 BPM. That’s it. No swing. No randomization. No memory. If you wanted to change the pattern? You had to turn a knob. If the synth warmed up? The timing drifted. A lot.Keyboardist Sarah Chen, who played on jazz fusion records in the late 70s, said in a 2017 forum post: "It was revolutionary for creating layered textures... but the timing would drift after 20 minutes of playing, requiring constant adjustment." That wasn’t a bug - it was the norm. Engineers didn’t see it as a flaw. They saw it as part of the sound. A slight lag here, a tiny jitter there - it made the music feel human, even when it was machine-generated.

Compare that to today’s software arpeggiators, which can reverse notes, randomize velocities, sync to a DAW, and store 100 patterns. Back then, you got one pattern, one tempo, one chance. That limitation forced creativity. You had to arrange your chords around what the machine could do. A four-note chord? Too much. A triad? Perfect. A single note? Boring. The best players learned to work within the box.

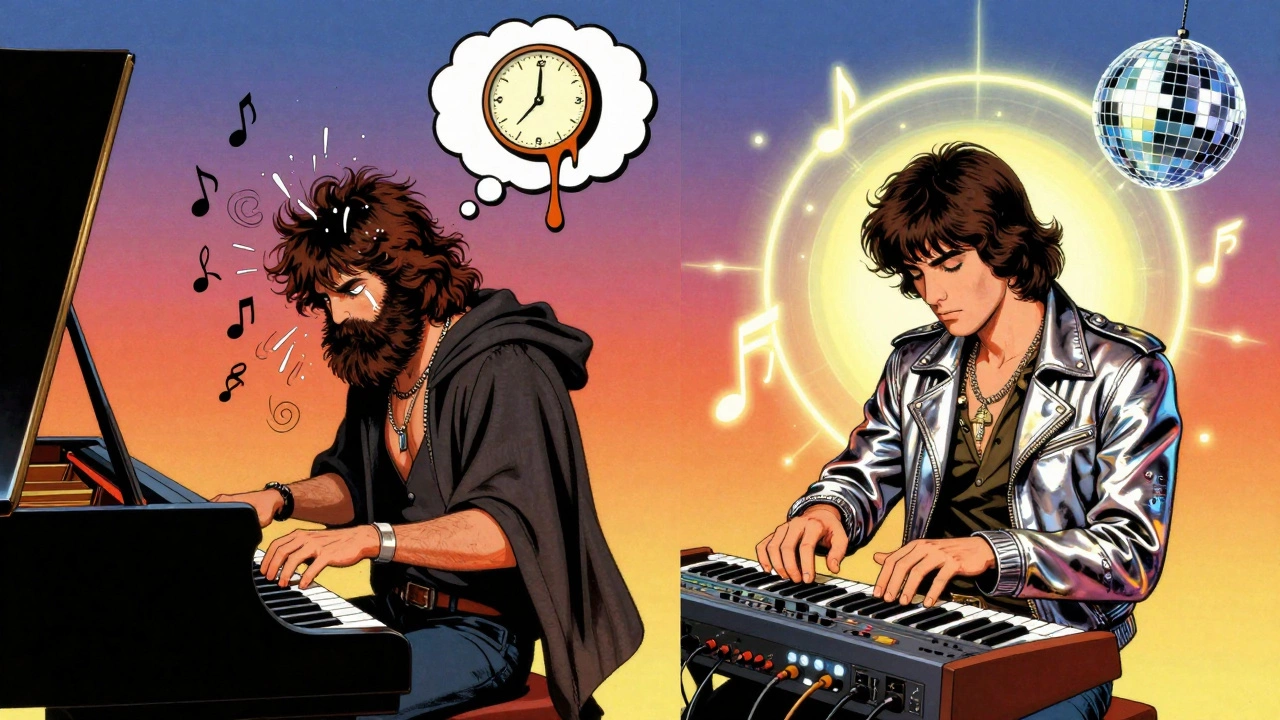

Prog Rock vs. Pop: Two Worlds, One Pulse

In progressive rock, arpeggiators were used sparingly - if at all. Bands like Genesis, Yes, and Emerson, Lake & Palmer preferred the human touch. Tony Banks famously refused to use them. "I preferred the human imperfection," he said in 1981. "Machines made everything too perfect and soulless." His performances on "Carpet Crawlers" and "Riding the Scree" were all manual - fingers moving fast, timing slightly off, just enough to feel alive.Meanwhile, in pop and disco, the arpeggiator became the heartbeat. Donna Summer’s "I Feel Love" (1977) didn’t use one - Giorgio Moroder programmed the sequence by hand using a Moog sequencer. But by 1979, the Roland Jupiter-4 a polyphonic analog synthesizer released in 1978 with one of the first built-in arpeggiators was everywhere. Blondie, Gary Numan, The Human League, and even The B-52’s used it to create that unmistakable, mechanical pulse. It wasn’t just rhythm. It was identity. A song without an arpeggiator in 1979 felt incomplete.

Why the split? Prog rock valued complexity, improvisation, and technical mastery. Pop wanted immediacy, repetition, and danceability. The arpeggiator didn’t care about genre. It just gave musicians what they needed: speed, consistency, and a sound no human could replicate live.

The Rise of a Niche Feature

In 1977, only 12% of new synthesizers had arpeggiators. By 1979? 38%. The Roland Jupiter-4 a polyphonic analog synthesizer released in 1978 with one of the first built-in arpeggiators was the turning point. It wasn’t the first synth with an arpeggiator - the Roland 184 had one in 1977 - but it was the first that musicians actually bought. It was affordable. It was reliable. It sounded good.Keyboard Magazine’s 1979 reader survey showed 68% of owners found arpeggiators "useful but limited." Only 22% called them "essential." That’s not because they weren’t powerful. It’s because they were still primitive. You couldn’t save patterns. You couldn’t change the order of notes. You couldn’t sync them to a drum machine. You had to play the chord, hold it, and pray the timing stayed steady.

Still, the demand grew. By 1980, 65% of new synths included one. Why? Because once you heard it, you couldn’t unhear it. The pulsing rhythm of "Take Me Out" by Franz Ferdinand? The opening of "Bizarre Love Triangle" by New Order? Those are direct descendants of the Jupiter-4’s arpeggiator. The sound had become a language.

Why It Still Matters Today

You might think this is all history. But in 2026, you can still hear it. The ARP Quadra a four-section synthesizer with a polyphonic arpeggiator that could layer bass, strings, and lead lines simultaneously was reissued by Behringer in 2023 - with the exact same arpeggiator circuit. Why? Because producers today spend hours chasing that "flawed" timing, that analog wobble, that slightly off-kilter groove that digital tools can’t replicate.A 2022 Reverb.com survey found that 78% of vintage synth buyers specifically looked for models with original 1970s arpeggiators. The Roland Jupiter-4 a polyphonic analog synthesizer released in 1978 with one of the first built-in arpeggiators sells for 300% more than the same model without one. Why? Because that little circuit didn’t just make music. It defined a moment.

Modern plugins like Arturia’s Arp2600 or UAD’s Roland Jupiter-8 emulation don’t just copy the sound - they copy the limitations. The timing drift. The note spacing. The way it only works with triads. That’s not a bug. It’s nostalgia. It’s authenticity. It’s proof that the late 1970s arpeggiator wasn’t just a gadget. It was the first time a machine gave a musician a voice they didn’t have before.

What Musicians Really Thought

Dr. Mark Vail, author of "The Synthesizer," called it "a crucial bridge between manual playing and automated sequencing." Richard James Burgess, who helped invent the Linn LM-1 drum machine, said it was "more immediately impactful on 1970s pop than the synthesizer itself." But not everyone was sold. Dr. Trevor Pinch called it "musically constraining," arguing it created clichés - and he wasn’t wrong. Listen to any late 70s pop track with a robotic arpeggio, and you’ll hear the same three-note pattern repeated endlessly.But that’s the point. It wasn’t meant to be creative. It was meant to be efficient. A producer in 1979 didn’t need a complex sequence. They needed a pulse. A beat. A hook. And the arpeggiator gave it to them in seconds.

Session keyboardist Mark Jenkins, who played on "Eat to the Beat," said: "The Jupiter-4’s arpeggiator saved me on ‘Atomic’ - I could play those pulsing chords with one hand while adding fills with the other, something impossible to do manually at that tempo." That’s the real legacy. It didn’t replace musicians. It gave them more time to be musicians.