Back in the early 1990s, if you wanted to make a hip-hop beat, you didn’t need a fancy studio. You just needed a sampler, a stack of old records, and a little nerve. Producers like Prince Paul, DJ Premier, and the Dust Brothers were building entire albums out of 3-second snippets of funk, soul, and rock. A snare from a James Brown track. A guitar riff from a 1970s jazz record. A vocal hook from a Motown single. They looped it, chopped it, flipped it - and made something completely new. But then the law caught up. And everything changed.

The Golden Age of Sampling

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, sampling wasn’t just a technique - it was a revolution. The E-mu SP-1200 and Akai MPC60 were the tools of choice. The SP-1200 gave you 1.2 seconds of sampling time per pad. The MPC60? A bit more - 750 milliseconds per sample. These weren’t mistakes. They were constraints that forced creativity. If you wanted a full 4-bar loop, you had to stack three or four samples together. You had to layer. You had to twist. You had to make magic out of fragments.

Albums like De La Soul’s 3 Feet High and Rising (1989) and the Beastie Boys’ Paul’s Boutique (1989) were built on hundreds of samples. Paul’s Boutique alone used over 100. Some came from The Beatles. Others from James Brown, Queen, and even Sesame Street. No one asked permission. Why? Because no one thought it mattered. Hip-hop was still seen as a fringe culture. Labels didn’t care. Artists didn’t worry. The cost to clear a sample? Sometimes $500. Often less. You’d call the label, negotiate, pay, and move on.

But this freedom wasn’t just about money - it was about culture. Sampling was how hip-hop spoke to the past. It was a way of quoting, honoring, and reimagining music that had been ignored by mainstream radio. It was collage. It was conversation. It was art.

The Biz Markie Case: When the Law Stepped In

All of that changed in 1991. Biz Markie, a rapper known for his playful style, used a 3-second piano loop from Gilbert O’Sullivan’s 1972 song “Alone Again” in his track “Alone Again.” No one asked for permission. No one paid. The sample was barely recognizable - just a few chords, looped twice.

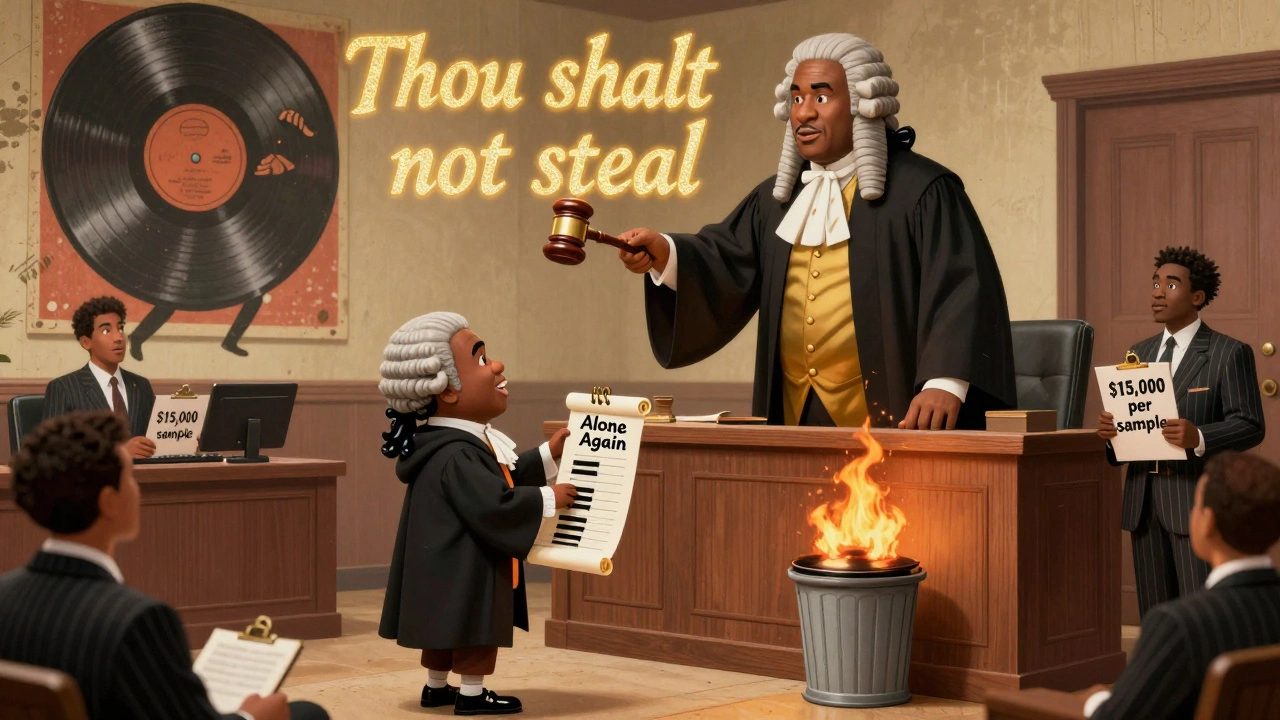

Then came the lawsuit. Grand Upright Music, Ltd. v. Warner Bros. Records Inc. The judge didn’t just rule against Biz Markie. He wrote: “Thou shalt not steal.” That’s not a legal phrase. That’s a biblical commandment. And it set the tone for everything that followed.

The court issued a preliminary injunction. The album was pulled from shelves. Biz Markie’s record label had to pay damages. But more than that - the ruling sent a message: even the tiniest sample, even if you couldn’t hear it, was theft. No exceptions. No gray area. Just a hard line.

Suddenly, every producer in the country had to stop and think. Was that 0.5-second horn stab from a 1973 funk record still fair use? What if you slowed it down? Pitched it up? Changed the tempo? The law didn’t care. The message was clear: if it’s copyrighted, you need permission. Even if it’s barely there.

The Cost of Creativity

Before 1991, clearing samples was a hassle. After? It became a financial nightmare.

By 1993, the average cost to clear one sample jumped from $500 to $15,000. For a major artist using a recognizable hook? $50,000. That’s not a typo. The Beastie Boys’ Paul’s Boutique would have cost over $1 million to legally clear in 1993. No label would risk that. No independent artist could afford it.

Prince Paul, who produced 3 Feet High and Rising, said he cleared 22 samples for that album at $350 each - $7,700 total. By 1993, he was paying $18,000 for 12 samples on a new project. He had to scrap half the album.

Independent artists were hit hardest. Major labels could absorb the cost. Indies? They had to choose: stop sampling, or stop making music. The result? Between 1991 and 1995, the number of independent hip-hop albums using samples dropped by 73%. Sampling didn’t disappear - it just got expensive. And corporate.

The Bridgeport Decision: The Final Nail

The 1991 Biz Markie case was shocking. But the 2005 Bridgeport Music, Inc. v. Dimension Films ruling was the death knell.

In that case, the hip-hop group N.W.A. used a 2-second guitar riff from the 1978 song “Get Off Your Ass and Jam” by Funkadelic. The sample was chopped, distorted, and buried under drums and bass. You couldn’t even hum it. But Bridgeport sued. And the Sixth Circuit Court ruled: “Get a license or do not sample.”

No matter how short. No matter how altered. No matter if the average listener couldn’t tell it was there. If it was sampled - it was infringement. Period. This overruled the old idea that tiny, unrecognizable uses were harmless. The “de minimis” defense - the legal principle that trivial copying isn’t illegal - was wiped out for sound recordings.

Music lawyer David Lowery called it “a chilling effect on musical creativity.” He wasn’t wrong. Producers stopped using real samples. They started hiring musicians to replay them. By 1997, 41% of the top 100 hip-hop tracks used “replayed” parts instead of actual samples. It was cheaper. It was safer. But it wasn’t the same.

A Split in the Law

But not everyone agreed.

In 2016, the Ninth Circuit Court ruled in VMG Salsoul, LLC v. Ciccone that Madonna’s use of a 0.23-second horn stab in “Vogue” was legal. The court said: “The average audience would not recognize the sample.” They explicitly rejected the Bridgeport rule. This created a split - two different laws in two different parts of the country.

Artists in California? They could sample tiny fragments. Artists in Ohio? Even a single note could get them sued. That confusion still exists today. 78% of music lawyers surveyed in 2022 told clients to avoid sampling entirely - no matter how small.

The Legacy: What Sampling Lost

The 1990s didn’t just change the law. It changed the sound.

Before the lawsuits, hip-hop was full of unexpected textures - a snippet of a theremin from a 1960s sci-fi movie, a snare from a 1970s children’s TV theme, a vocal ad-lib from a gospel record. Those sounds were the heartbeat of the genre. After? Beats became cleaner. More predictable. More expensive. More corporate.

Sampling didn’t die. But it got harder. And more lonely. The artists who grew up with a stack of records and a sampler couldn’t compete with producers who had studio time, lawyers, and label budgets. The music became less experimental. Less risky. Less alive.

Today, you can still hear traces of that era - in Kanye West’s early albums, in Madlib’s beat tapes, in the underground scenes that still use vinyl and samplers. But the golden age? It’s gone. And the reason isn’t because technology failed. It’s because the law decided creativity wasn’t worth the risk.

What Comes Next?

Now, in 2026, AI tools are offering a new path. Some platforms let producers drag and drop a sample, and the AI automatically clears it - paying royalties, verifying rights, and logging everything on a blockchain. 63% of producers under 25 are already using these tools. It’s not perfect. But it’s faster. Cheaper. Safer.

Maybe the future won’t be about stealing from records. Maybe it’ll be about rebuilding from the ground up - with permission built in from the start. But for those who remember the 1990s? The music that came before feels like a lost language. A time when you could make art out of someone else’s echo - and no one called it theft.

It wasn’t lawless. It was alive.